Every year, thousands of patients in the U.S. receive the wrong medication-not because the pharmacist made a mistake with the drug, but because they gave it to the wrong person. This isn’t rare. It’s systemic. And the fix? Simple, but often ignored: using two patient identifiers before handing out any prescription.

Why Two Identifiers? It’s Not Just a Rule-It’s a Lifesaver

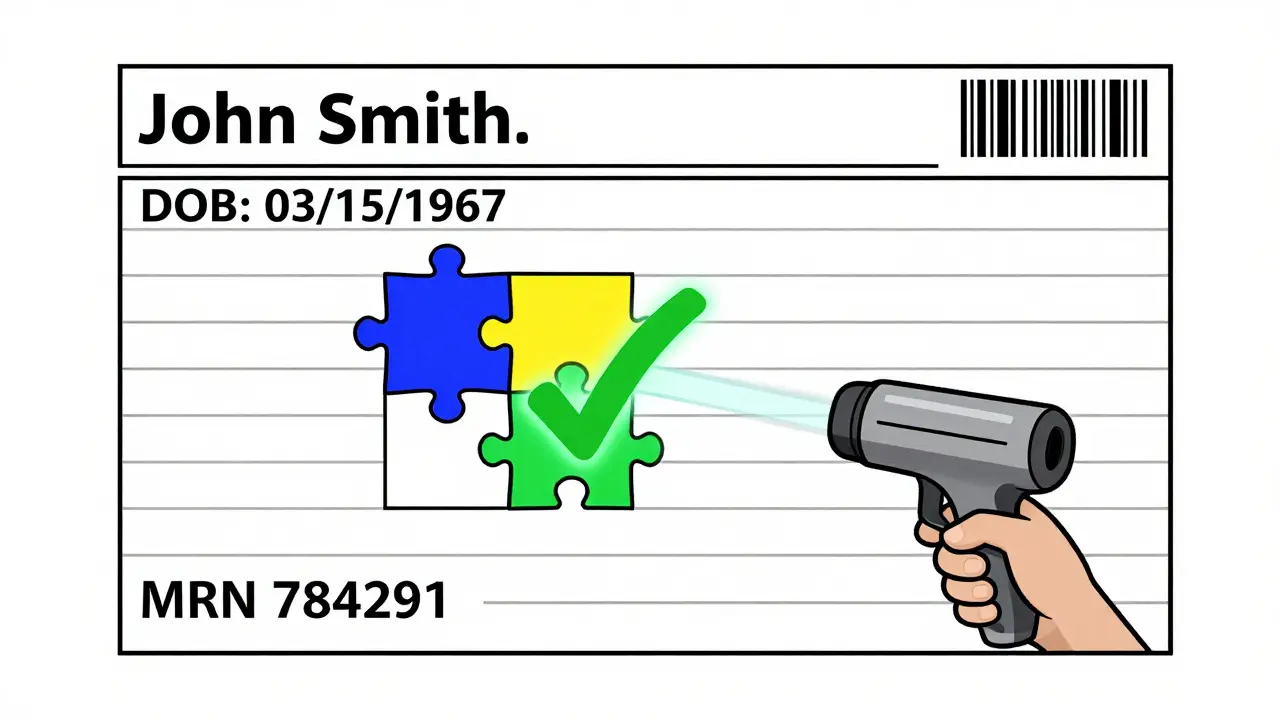

The Joint Commission made this mandatory in 2003. Not as a suggestion. Not as a best practice. As a patient safety goal. NPSG.01.01.01. If you work in a pharmacy in the U.S., you’re legally required to verify at least two unique identifiers before dispensing any medication. And yet, compliance is still spotty-especially in busy community pharmacies. Why does this matter? Because names aren’t unique. John Smith? There are over 37,000 in the U.S. alone. Same with birthdates. Two people born on May 12, 1978? Not uncommon. Mix that with duplicate records, misspelled names, or patients using nicknames, and you’ve got a recipe for disaster. A 2020 study in JMIR Medical Informatics found that up to 10% of serious drug-drug interaction alerts go undetected because systems can’t match patients correctly. That’s about 6,000 people a year getting medications they shouldn’t. Some of those reactions are fatal.What Counts as a Valid Identifier?

Not everything you think works, actually does. The Joint Commission is clear: room number is not an acceptable identifier. Neither is “the guy in bed three.” Those are locations, not identities. Acceptable identifiers include:- Full legal name

- Date of birth

- Assigned medical record number

- Phone number

- Address (if consistently used and verified)

Manual Verification Isn’t Enough-Here’s Why

Most community pharmacies still rely on pharmacists asking patients: “What’s your name?” and “When were you born?” Then they check the screen. Sounds simple. But humans are bad at this. A 2023 survey by the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP) found that 63% of pharmacists admit to occasionally skipping full verification during peak hours. Why? Time pressure. Long lines. A patient who says, “I’m John Smith, born in ’72,” and the pharmacist doesn’t double-check because they’ve seen him before. That’s how errors happen. One documented case from Altera Health involved a woman who was misidentified across five different specialty clinics. Each doctor created a new record because her name was entered slightly differently each time. She ended up on two different blood thinners at the same time-neither doctor knew the other had prescribed one. She nearly bled out.

Technology Fixes What Humans Can’t

The most effective way to prevent these errors? Technology. Barcode scanning at the point of dispensing and administration cuts medication errors by 75%, according to a 2012 study in the Journal of Patient Safety. Here’s how it works:- The pharmacist scans the patient’s wristband (with barcode containing name and DOB).

- The system scans the medication label.

- If the patient and drug don’t match, an alert pops up-before the pill leaves the counter.

What About Double Checking? Does It Work?

Some pharmacies have a rule: two staff members must verify every high-risk medication. Sounds smart. But a 2020 review in BMJ Quality & Safety found no solid proof it reduces errors. Why? Because if both people are looking at the same screen, reading the same name, and both assume the other checked, you get confirmation bias. You don’t get independent verification. You get two people missing the same mistake. The real win? Technology that forces the check. Not human memory.What Happens When You Don’t Follow the Rules?

The Joint Commission doesn’t just write guidelines-they enforce them. In 2023, non-compliance with the two-identifier rule was the third most common violation in hospital surveys. And it’s not a slap on the wrist. If you fail, you risk losing accreditation. Lose accreditation, and you lose Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement. That’s not a small penalty. It’s existential for many clinics. The 21st Century Cures Act and CMS rules now tie accurate patient identification to nationwide data sharing. If your system can’t match patients correctly, you can’t exchange records. That means no e-prescribing, no lab results, no continuity of care.

Real Stories: When the System Failed

One patient was brought to the ER unconscious. The hospital couldn’t find his record. So they created a new one. Days later, they discovered he had a full medical history under his middle name. He was allergic to penicillin. The new record didn’t have that. He was almost given it. Another case: a patient got a double dose of insulin because the pharmacy system merged two records with similar names and birth years. He went into hypoglycemic shock. These aren’t outliers. They’re symptoms of a broken system.How to Do It Right: A Practical Checklist

If you’re a pharmacist, pharmacy tech, or manager, here’s what you need to do:- Always use two identifiers-never one.

- Never use room number, location, or “the patient in chair 4.”

- Document every verification in the electronic record.

- Use barcode scanning if available-don’t rely on manual checks.

- Train staff every quarter. Complacency kills.

- Use EMPI systems to reduce duplicate records.

- Implement timeouts before high-alert meds (like opioids, insulin, blood thinners).

The Future Is Here-But Only If We Use It

The Office of the National Coordinator for Health IT is piloting a universal patient identifier system in 2025. It’s not perfect. Privacy concerns are real. Costs are high-up to $1.8 million per 100-bed hospital to fully integrate. But here’s the truth: we’re already paying the price. $40 million a year per large hospital system goes to fixing duplicate records and correcting errors. Thousands of patients are hurt. Some die. The two-identifier rule isn’t about bureaucracy. It’s about not killing someone because you assumed their name was correct. It’s time to stop treating it like a checkbox. Treat it like the last line of defense it is.What are the two patient identifiers required by law in pharmacies?

The Joint Commission requires at least two unique, person-specific identifiers such as full name and date of birth, medical record number, or phone number. Room number, location, or generic labels like "the patient in bed 3" are not acceptable.

Why is using two identifiers better than just one?

A single identifier like a name can be shared by hundreds of people. Adding a second identifier, like date of birth or medical record number, reduces the chance of mixing up patients by over 90%. It’s a simple math fix: two data points are far harder to match incorrectly than one.

Do barcode scanners really reduce errors?

Yes. Studies show barcode scanning reduces medication errors reaching patients by 75%. When the system matches the patient’s wristband barcode to the medication label, it catches mismatches before the drug leaves the counter. Manual checks alone don’t catch nearly as many errors.

Why do some pharmacists skip the two-identifier check?

Time pressure. Long lines. Staff shortages. In community pharmacies, especially during peak hours, some pharmacists rely on memory or familiarity with patients. But that’s risky-people change names, birthdays get misremembered, and duplicate records exist. Skipping verification increases the chance of a fatal error.

What happens if a pharmacy doesn’t follow the two-identifier rule?

The Joint Commission can cite the pharmacy for non-compliance, which affects accreditation. Losing accreditation means losing Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement-something many pharmacies can’t survive financially. It also opens the door to lawsuits if a patient is harmed.

Are there alternatives to manual verification?

Yes. Barcode scanning, biometric systems (like palm-vein recognition), and Enterprise Master Patient Index (EMPI) systems that link all patient records under one ID are far more reliable. Biometric systems match patients with 94% accuracy, compared to 17% in systems without EMPI.

How do duplicate medical records contribute to errors?

When a patient has multiple records due to name variations or data entry errors, their allergies, medications, and conditions aren’t visible to every provider. A patient might be prescribed a drug they’re allergic to because one record shows the allergy and another doesn’t. This happens in 8-12% of patient records in systems without strong identification tools.

Comments (8)

Chloe Hadland

January 24, 2026 AT 05:53

just saw a pharmacist hand someone their meds without asking for dob once and my heart dropped. i swear i felt the whole room hold its breath. we’re literally gambling with lives here and people act like it’s just paperwork.

Sawyer Vitela

January 26, 2026 AT 01:24

barcodes aren't optional. if your pharmacy doesn't use 'em, you're not a pharmacy-you're a liability waiting for a lawsuit.

Shanta Blank

January 27, 2026 AT 01:44

oh honey, i’ve seen pharmacists yell ‘NAME AND BIRTHDAY’ like they’re calling out a bingo number while scrolling tiktok. it’s not compliance-it’s theater. and the patient’s just nodding along like they’re in a cult. we’re not saving lives here, we’re performing them.

one time i walked in with ‘jess’ on my insurance card and ‘jessica’ on my id. they handed me my husband’s blood pressure med. i didn’t notice until i got home and my hands were shaking. turns out he’s got a different DOB, same last name, same damn town. they didn’t even blink.

and don’t get me started on the ‘oh we’ve seen you before’ crowd. i’ve been in three different ERs under three spellings of my name. one time i got a morphine drip because they thought i was my cousin who had cancer. i had a cold. i cried for an hour. no one apologized. just said ‘oops, system glitch.’

we’re not talking about minor mix-ups. we’re talking about people dying because someone thought ‘john smith’ was a unique identifier. it’s not laziness-it’s negligence dressed up as tradition.

and yes, biometrics work. palm veins? yeah. i’ve seen it in VA hospitals. no name, no dob, no guesswork. just scan and go. why can’t community pharmacies afford that? because they’d rather save $2k on a scanner than pay $2m in wrongful death settlements.

the system isn’t broken. it’s being ignored. and the people paying the price? they’re the ones who can’t afford to be wrong.

so yeah, i’m dramatic. but i’ve seen what happens when the checklist gets skipped. and i’ll scream about it until the whole damn pharmacy runs on biometrics or gets shut down.

Kevin Waters

January 28, 2026 AT 13:27

the checklist works if you actually use it. i’m a tech at a small pharmacy and we started doing verbal verification out loud-patient says it, we say it back, then we check the screen. it adds 10 seconds but we’ve had zero errors since. no fancy scanners, just discipline.

and honestly? patients appreciate it. they feel seen. one lady told me ‘you’re the first one who actually asked me twice.’ that stuck with me.

Amelia Williams

January 28, 2026 AT 23:10

i know it sounds boring but this is the stuff that keeps people alive. i used to work in a clinic where they skipped the second identifier because ‘everyone knew each other.’ then a guy got the wrong chemo. he didn’t make it home. his wife still posts on the clinic’s fb page every year on his birthday. just saying ‘i wish they’d asked his birthdate.’

it’s not about rules. it’s about remembering that behind every name is a person who trusts you with their life.

and yes, i cried reading this. not because it’s sad-because it’s so avoidable.

Jamie Hooper

January 30, 2026 AT 05:40

barcodes are the bare minimum. why are we still using paper records in 2025? my mum got her insulin mixed up because the system thought she was her sister. same name, same town, different middle initial. no one even noticed until she passed out at the grocery store.

we’re all just hoping someone else checks the damn box.

Himanshu Singh

January 31, 2026 AT 23:42

we think of safety as a rule… but it’s really a promise. a quiet vow between the person handing you the pill and the person receiving it: ‘i see you, i know you, i won’t let you be someone else.’

when we reduce identity to a checkbox, we reduce humanity to a glitch. and glitches… get fixed. people don’t.

biometrics aren’t futuristic. they’re faithful.

🙂

Sharon Biggins

February 1, 2026 AT 19:25

i work at a small pharmacy and we just started using a simple barcode scanner last month. it cost like $800. we used to skip checks during lunch rush. now we dont. one lady came in crying last week because she used to get the wrong meds all the time. she said ‘i finally feel safe here.’ i almost cried too.

its not about tech. its about care.