Imagine a food safety inspector who used to work for a major meatpacking company. Now they’re supposed to enforce rules that could shut down that same company. What happens when their loyalty shifts-from protecting consumers to protecting the industry they once worked for? This isn’t fiction. It’s regulatory capture, and it’s happening right now in agencies meant to keep us safe.

What Is Regulatory Capture?

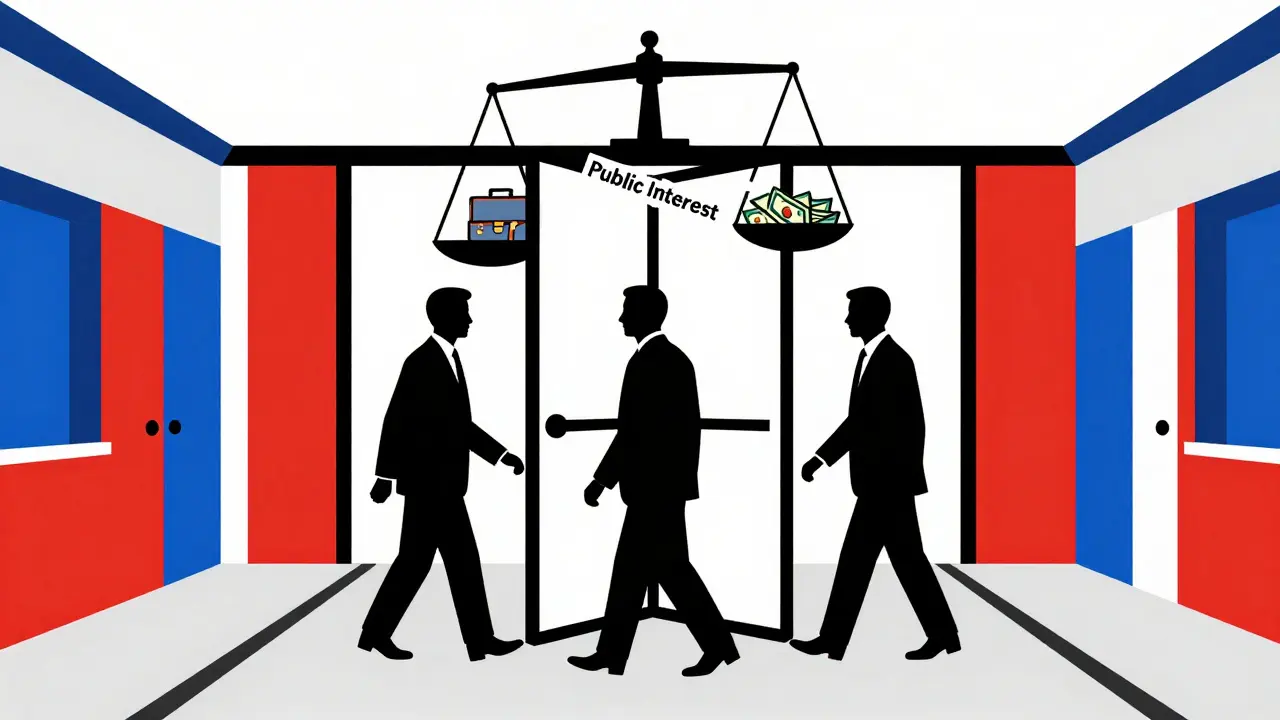

Regulatory capture happens when the agencies created to protect the public end up serving the industries they’re supposed to regulate. Instead of acting in the public interest, these agencies start making decisions that benefit big corporations-often at the expense of consumers, workers, or the environment. It’s not always about bribery or corruption. Sometimes it’s quieter. Regulators spend so much time talking to industry experts, attending their conferences, and relying on their data that they start thinking like them. They begin to believe that what’s good for the company is good for everyone. That’s cultural capture. Other times, it’s money-lobbyists fund campaigns, former regulators take high-paying jobs at the companies they once policed, and agencies depend on industry funding to stay open. That’s materialist capture. The term was first clearly described by economist George Stigler in 1971. He pointed out that regulation doesn’t emerge to help the public. It emerges because industries want it-to block competition, avoid accountability, or lock in profits. And over time, they get it.How It Works: The Three Main Mechanisms

There are three ways regulatory capture takes hold, and they often work together. First, the revolving door. When a regulator leaves government to join the industry they once oversaw, it sends a signal: play nice now, and you’ll be rewarded later. Between 2008 and 2018, 53% of senior U.S. Department of Defense officials went to work for defense contractors within a year of leaving. At the SEC, 87% of the staff regulating Wall Street had direct ties to the firms they supervised. That’s not coincidence. It’s a system. Second, information asymmetry. Regulators can’t possibly understand every technical detail of modern industries-like cryptocurrency, pharmaceuticals, or nuclear energy. So they rely on the companies themselves to provide data, models, and safety reports. But what if those reports are biased? What if they hide risks? In 2020, the FAA allowed Boeing to conduct 96% of the safety reviews for the 737 MAX-on its own. The result? 346 people died. Third, concentrated benefits, dispersed costs. A few companies make billions from a rule. Millions of people pay a little extra-$33 a year for sugar, $50 for prescription drugs, $100 for higher energy bills. No one person feels it enough to protest. But the industry? They’ll spend millions to protect that profit. In the U.S., industry lobbying spending is 17 times higher per person than consumer advocacy groups. The math is rigged.Real-World Examples: From Sugar to Airlines

The sugar industry in the U.S. is a textbook case. The government imposes tariffs and quotas that keep domestic sugar prices three times higher than the global market. Every American household pays about $33 extra per year. That’s $3.9 billion total. Who benefits? Just 4,318 sugar producers. They make $1.2 billion more in profit. No one’s marching in the streets. But they’re paying. In energy, UK regulator OFGEM approved £17.8 billion in consumer bill hikes between 2015 and 2020 to fund grid upgrades. But energy companies kept profit margins at 11.2%-well above the 6.8% cap. Consumers footed the bill. Regulators didn’t push back. The 2008 financial crisis was fueled by regulatory capture at the SEC. The agency had close ties to Wall Street firms. Staff moved between regulators and banks. Oversight was weak. Derivatives worth $23 trillion were left unchecked. When the system collapsed, ordinary people lost homes and jobs. The bankers? They got bailed out. Even the FDA has been accused. Former employees frequently join pharmaceutical companies. A 2022 report found that 73% of former EPA officials who left government went to work for fossil fuel firms. That’s not just a job change-it’s a shift in priorities.

Why It’s So Hard to Fix

You’d think the solution is simple: ban former regulators from working in the industries they oversaw. But it’s not that easy. The U.S. has a 1978 law requiring a “cooling-off period” before officials can join regulated industries. But 41% of violations go unpunished. Why? Because enforcement is weak. And because the people who should be enforcing it often have the same ties. The EU tried transparency. They created a lobbying register. But only 32% of big corporations actually comply. It’s like asking a thief to report their own crimes. Then there’s the problem of complexity. Regulating AI, blockchain, or gene therapy requires deep technical knowledge. The industry has the experts. The government doesn’t. So regulators hire consultants from the same firms they’re supposed to regulate. It’s a loop. Political resistance is another barrier. Between 2015 and 2022, 78% of proposed anti-capture laws failed in Congress. Why? Because the industries that benefit from the status quo spend billions to kill reform.What’s Being Done-and What’s Working

Some places are fighting back. New Zealand introduced an independent process for reviewing new regulations. Between 2016 and 2022, industry-preferred rules dropped from 68% to 31%. How? By forcing agencies to justify every rule to the public and include consumer voices. Canada trained its regulators in ethical decision-making. After the program, industry meetings got 27% shorter. Public consultations went up by 43%. Regulators learned to ask harder questions. In France, the “Citizen’s Convention on Climate” brought together 150 randomly selected citizens to draft climate policy. Their recommendations reduced energy industry influence on the final plan by 52%. No lobbyists. Just people. The U.S. Federal Trade Commission launched its own Regulatory Capture Initiative in March 2023. It now requires full disclosure of all industry contacts and created a new Office of Regulatory Integrity with a $23 million budget. Time will tell if it’s enough.

What You Can Do

You don’t need to be a policymaker to fight regulatory capture. Here’s what you can do:- Ask questions. When a drug price spikes, ask: Who approved this? Who advised the FDA?

- Support watchdog groups. Organizations like Public Citizen, Consumer Reports, and the Center for Responsive Politics track industry influence. Donate. Volunteer.

- Demand transparency. Push your representatives to require public disclosure of all meetings between regulators and industry reps.

- Vote for candidates who won’t take industry money. Campaign finance reform isn’t just about fairness-it’s about keeping regulators independent.

The Bigger Picture

Regulatory capture isn’t a glitch in the system. It’s a feature. It’s what happens when power is concentrated, accountability is weak, and the public is distracted. The World Bank calls it a systemic risk. The OECD says it costs member countries 0.8% of GDP every year-billions lost to inefficiency, higher prices, and unsafe products. And it’s getting worse. The rise of AI-powered lobbying-where bots generate 17,000 fake public comments per hour-is making it easier than ever for industries to drown out real voices. But public trust hasn’t disappeared. In 2023, 78% of Americans said they were deeply concerned about industry influence on regulators. That’s a spark. And sparks can turn into fire. The question isn’t whether regulatory capture exists. It’s whether we’re willing to do something about it.Is regulatory capture the same as corruption?

Not always. Corruption involves illegal acts like bribery or kickbacks. Regulatory capture is often legal-it’s about influence, access, and culture. A former regulator taking a job at a company they once oversaw isn’t breaking the law. But it still distorts outcomes. It’s the gray area where power gets bent, not broken.

Which industries are most affected by regulatory capture?

The financial sector leads with 67% of countries showing high capture risk, according to the World Bank. Energy (58%) and pharmaceuticals (52%) follow closely. These industries have high profits, complex regulations, and deep pockets for lobbying. Tech and agriculture are rising fast, especially as new technologies like AI and gene editing outpace regulation.

Can regulators ever be truly independent?

Yes-but only with strong safeguards. Independent funding (not tied to industry fees), mandatory cooling-off periods, public disclosure of all meetings, and citizen oversight panels help. New Zealand and Canada have shown it’s possible. The key is reducing the industry’s monopoly on information and influence.

Why don’t voters punish politicians who enable regulatory capture?

Because the effects are hidden. You don’t see the lobbyist in the room. You don’t see the regulator who used to work for the company. You just see higher prices, slower recalls, or unsafe products. The connection isn’t obvious. Meanwhile, politicians get campaign donations and praise from powerful industries. It’s a silent deal-until someone gets hurt.

How does regulatory capture affect everyday people?

It hits your wallet, your health, and your safety. You pay more for sugar, fuel, and medicine. You’re exposed to riskier drugs because approvals were rushed. You live near a factory that’s allowed to pollute because regulators deferred to the company’s ‘safety report.’ It’s not conspiracy-it’s policy shaped by money and access.

Comments (9)

Dylan Smith

December 16, 2025 AT 18:12

This is exactly why I stopped trusting any federal agency. They’re not there to protect us-they’re there to protect the corporations that fund them. I’ve seen it firsthand in my job. The same people who used to audit drug safety now work for the pharma giants. No one talks about it because everyone’s too scared to speak up.

And don’t get me started on the revolving door. It’s not a loophole-it’s the entire system.

It’s not corruption. It’s legal theft.

Mike Smith

December 17, 2025 AT 12:38

Thank you for this thorough and well-researched breakdown. Regulatory capture is one of the most insidious threats to democratic governance, yet it rarely makes headline news because it operates beneath the surface of what we consider 'corruption.' The structural nature of this problem-where incentives are aligned against public interest-requires systemic reform, not just moral outrage.

Initiatives like New Zealand’s independent review process and Canada’s ethical training for regulators offer tangible hope. We must demand similar structural safeguards here, not just symbolic gestures.

Ron Williams

December 17, 2025 AT 15:21

Been thinking about this a lot since the 737 MAX crash. I used to fly a lot for work. Now I just take trains. Not because I’m scared, but because I don’t trust the people who are supposed to be watching.

It’s weird how normal this all feels now. Like we’ve just accepted that the fox is in charge of the henhouse-and it’s not even a secret. Everyone knows it. But nobody does anything.

Kinda makes you wonder if we’re past the point of fixing it.

Colleen Bigelow

December 18, 2025 AT 02:17

THIS IS THE NEW WORLD ORDER. THEY WANT YOU BROKE, SICK, AND STUPID. THE FDA, THE FAA, THE SEC-ALL CONTROLLED BY THE SAME FEW BILLIONAIRES WHO OWN THE MEDIA, THE BANKS, AND THE MILITARY INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX. THEY LET BOEING KILL 346 PEOPLE BECAUSE IT WAS CHEAPER THAN SAFETY. THEY LET PHARMA RAISE DRUG PRICES BECAUSE THEY OWN THE LAWMAKERS.

THEY’RE NOT JUST CAPTURED-THEY’RE THE OWNERS. AND THEY’RE USING AI BOTS TO FLOOD THE COMMENTS WITH PRO-CORPORATE RUBBISH. YOU THINK THIS IS COINCIDENCE? IT’S A PROGRAM. A PLAN. A SYSTEM TO ERASE DEMOCRACY.

STOP VOTING. START ORGANIZING. OR YOU’LL BE THE NEXT ONE PAYING FOR THEIR PROFITS.

Cassandra Collins

December 19, 2025 AT 13:48

ok but what if the regulators are just dumb and the industry is just way smarter? like how are they supposed to understand blockchain or ai if they never went to college for it? its not that theyre bought its that theyre outgunned. also why is everyone mad at the people who took jobs after govnt? i mean i’d take the money too 😐

Kitty Price

December 20, 2025 AT 21:02

So much truth here. 🫠 I work in public health and I’ve seen the same thing with tobacco and sugar lobbying. They show up with fancy slides, paid studies, and ‘experts’ who all used to work at the FDA. We’re supposed to trust them? No thanks.

Also, the Citizen’s Convention in France? That’s genius. More of that. Less lobbyists. More real people.

❤️🩹

Souhardya Paul

December 21, 2025 AT 19:48

Interesting how the solutions are so simple in theory-transparency, cooling-off periods, public input-but so hard to implement. Why? Because the people who benefit from the current system are the ones writing the rules.

I think the real question is: who’s going to pay for independent regulators? If we don’t fund them properly, they’ll keep relying on industry for data, experts, and even office space. It’s not just about ethics-it’s about resources.

Also, the 17,000 fake comments per hour? That’s not just manipulation. That’s warfare.

Josias Ariel Mahlangu

December 22, 2025 AT 05:29

Regulatory capture is not unique to the United States. In South Africa, mining companies have long influenced environmental regulators. The same patterns: revolving doors, data manipulation, and silence from the public. The cost is not only economic-it is ecological, and human.

What is needed is not more laws, but independent oversight bodies with teeth, funded by public treasuries-not industry fees.

anthony epps

December 22, 2025 AT 07:12

so basically the system is rigged and no one can fix it?