Why do some people struggle to lose weight even when they eat less and exercise more? It’s not about willpower. It’s about biology. Obesity isn’t just a result of eating too much or moving too little-it’s a complex disease where the body’s natural systems for controlling hunger and energy use break down. The science behind this is clear: obesity pathophysiology involves a broken feedback loop between your brain and your fat cells, turning normal appetite control into a constant drive to eat.

The Brain’s Hunger Control Center

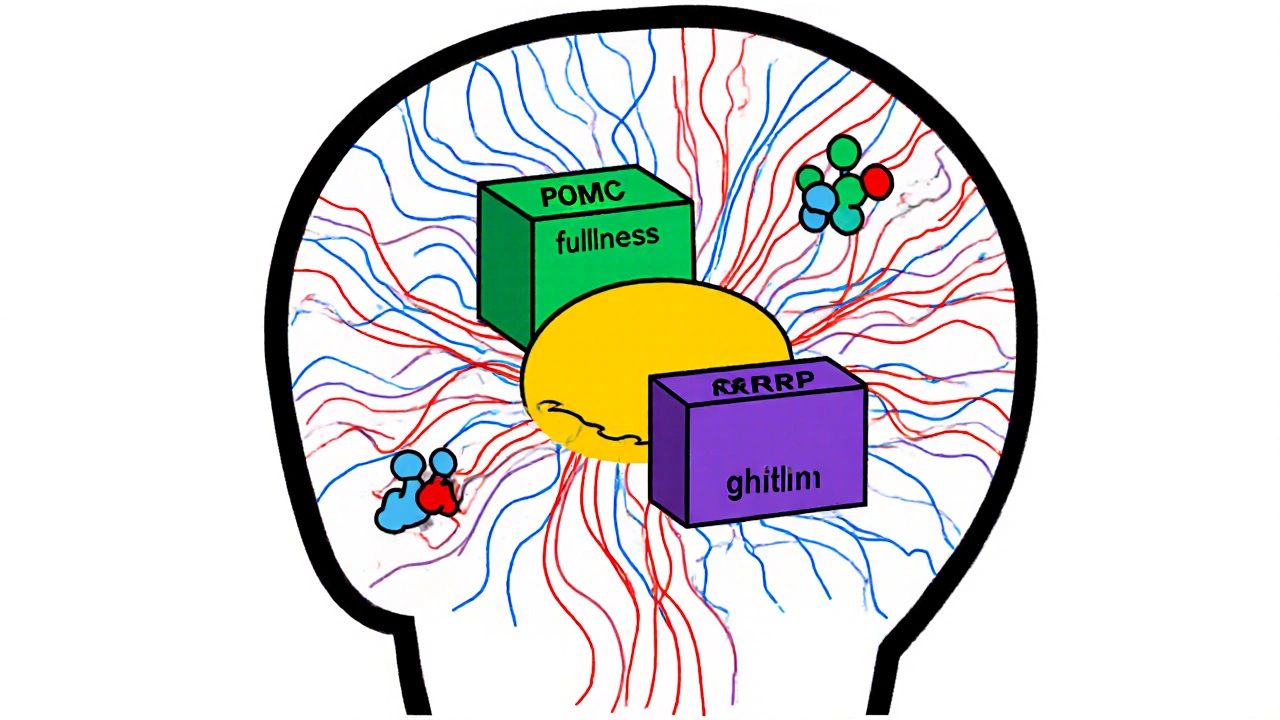

At the heart of this system is a tiny region in your brain called the arcuate nucleus, part of the hypothalamus. This area acts like a thermostat for your body weight. It has two opposing teams of neurons: one that tells you to stop eating, and another that screams for more food. The first team, made up of POMC neurons, releases a signal called alpha-MSH. This signal tells your brain you’re full. When it works right, it cuts your food intake by 25-40%. The second team, NPY and AgRP neurons, does the opposite. They trigger hunger. When these neurons fire, you feel an intense urge to eat-even if you just finished a meal. In lab studies, turning on just these neurons made mice eat 300-500% more food in minutes. These neurons don’t work alone. They listen to signals from your body. Fat cells send out leptin, a hormone that tells your brain, “I have enough stored energy.” In a lean person, leptin levels sit between 5-15 ng/mL. In someone with obesity, those levels jump to 30-60 ng/mL. You’d think more leptin would mean less hunger. But here’s the problem: the brain stops listening. That’s called leptin resistance. It’s not that the body doesn’t make enough leptin-it’s that the signal gets drowned out, like a smoke alarm stuck in a noisy room.The Hormonal Messengers

Leptin isn’t the only hormone involved. Insulin, released after meals, also tells your brain to cut back on eating. In healthy people, fasting insulin levels are around 5-15 μU/mL. After eating, they spike to 50-100 μU/mL, helping to suppress appetite. But in obesity, insulin’s signal gets weaker too. This is called central insulin resistance-and it’s just as damaging as leptin resistance. Then there’s ghrelin, the only known hunger hormone. Ghrelin rises before meals, peaking at 800-1000 pg/mL, and directly activates those hunger neurons. In people with obesity, ghrelin doesn’t drop as much after eating. That means the “I’m hungry” signal lingers longer. You’re not just eating because you’re hungry-you’re eating because your body keeps sending the wrong signal. Another key player is pancreatic polypeptide (PP), released after meals to slow digestion and reduce appetite. But in 60% of people with diet-induced obesity, PP levels are abnormally low-between 15-25 pg/mL instead of the normal 50-100 pg/mL. This means even after eating, your brain doesn’t get the full message that the meal is done.

The Broken Pathways

Inside the brain, these hormones talk to neurons through chemical pathways. One of the most important is the PI3K/AKT pathway. It’s the main line of communication for both leptin and insulin. When leptin binds to its receptor, it triggers this pathway, which shuts down hunger. But in obesity, this pathway gets blocked. Studies show that if you block PI3K in the brain, leptin loses its ability to reduce food intake entirely. That’s not a small glitch-it’s a total system failure. Another pathway, JNK, gets overactivated in obesity. It doesn’t cause hunger directly, but it makes the brain ignore leptin. Think of it like a firewall that’s been hacked-signals from fat cells can’t get through. Meanwhile, the mTOR system, which normally helps regulate energy balance, becomes less responsive. In older adults, this slowdown contributes to weight gain, even without changes in diet. Even serotonin, a neurotransmitter often linked to mood, plays a role. Some experts say it reduces appetite by activating POMC neurons. Others argue it works by silencing the hunger neurons. The truth? Both might be true. The exact mechanism is still debated, but one thing isn’t: serotonin signaling is disrupted in obesity.Why Weight Loss Feels Impossible

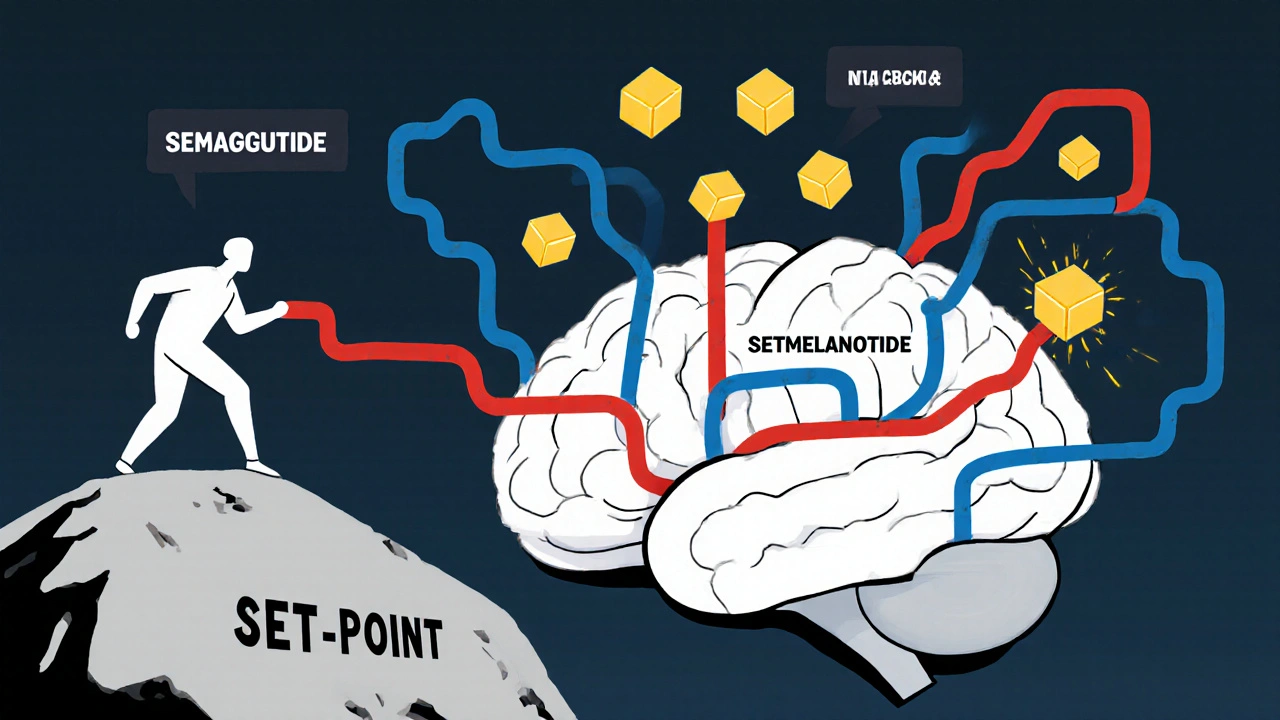

When you lose weight, your body fights back. Fat cells shrink, so they release less leptin. Your brain interprets this as starvation. Ghrelin rises. Metabolism slows. You feel hungrier, colder, and more tired. This isn’t laziness. It’s biology. Your body is trying to return to its old, heavier state. This is why most diets fail. You lose 10 pounds, then gain back 12. The brain’s set point-the weight it thinks you should be-hasn’t changed. It’s like trying to push a boulder uphill. The system is designed to resist change. Even hormonal shifts like menopause make it harder. After menopause, estrogen drops. In women, estrogen helps regulate appetite and energy use. When it falls, women gain more belly fat, eat 12-15% more, and burn 30% less energy at rest. It’s not about age-it’s about hormones.

What’s New in Treatment

The good news? Science is catching up. Drugs like semaglutide (Wegovy) and setmelanotide target these broken pathways directly. Semaglutide mimics GLP-1, a gut hormone that slows digestion and reduces appetite. In clinical trials, it helped people lose an average of 15% of their body weight. Setmelanotide works on the melanocortin-4 receptor-the same receptor activated by POMC neurons. In rare genetic forms of obesity, it can lead to 20%+ weight loss. In 2022, researchers discovered a new group of neurons near the hunger and fullness centers that, when stimulated, shut down eating within two minutes. This wasn’t just about suppressing appetite-it was about overriding the system entirely. It’s a breakthrough that could lead to new drugs that don’t just reduce hunger but reset the brain’s weight control system.The Bigger Picture

Obesity affects 42.4% of U.S. adults. Globally, it’s tripled since 1975. It’s not a lifestyle choice-it’s a chronic disease with deep biological roots. The $173 billion annual cost in the U.S. isn’t just for medications and surgeries. It’s for diabetes care, heart disease, joint replacements, and lost productivity-all tied to this one condition. Understanding the pathophysiology changes everything. We stop blaming people. We stop telling them to “just eat less.” Instead, we treat obesity like we treat high blood pressure or diabetes: with science, with medication, with long-term management. The future isn’t about willpower. It’s about fixing the broken signals in the brain. And that’s exactly what the next generation of treatments is designed to do.Is obesity caused by eating too much?

No-not primarily. While overeating plays a role, obesity is driven by a breakdown in the body’s biological systems that regulate hunger, fullness, and energy use. People with obesity often have hormonal imbalances, brain signaling defects, and metabolic slowdowns that make it extremely hard to control food intake, even when they try. It’s not a lack of discipline-it’s a medical condition.

What is leptin resistance?

Leptin resistance is when the brain stops responding to leptin, the hormone that signals fullness. In obesity, fat cells produce more leptin, but the brain doesn’t recognize it. This tricks the brain into thinking the body is starving, so it increases hunger and slows metabolism. Leptin resistance is the most common cause of weight gain in people with common obesity-not a shortage of leptin, but an inability to use it.

Why do I feel hungrier after losing weight?

After weight loss, your fat cells shrink and produce less leptin. Your stomach releases more ghrelin. Your metabolism slows down. All of this tells your brain you’re in danger of starvation. This is a survival mechanism-it’s not your fault. That’s why many people regain weight: their biology is working against them. New medications like semaglutide help by mimicking natural fullness signals to override this response.

Can obesity be reversed with diet and exercise alone?

Some people can, but for many, it’s not enough. The body’s biological systems resist long-term weight loss. Studies show that over 80% of people who lose significant weight regain it within five years. That’s because the brain and hormones are still signaling for weight regain. For those with severe obesity or metabolic dysfunction, medical treatments that target appetite regulation are often necessary for lasting results.

Are weight-loss drugs safe?

Yes, when used under medical supervision. Drugs like semaglutide and tirzepatide have been tested in tens of thousands of people over years. Side effects like nausea or digestive issues are common at first but usually fade. Serious risks are rare. These medications don’t replace healthy habits-they support them by reducing overwhelming hunger and cravings. For many, they’re life-changing.

Does genetics play a role in obesity?

Absolutely. Over 200 genes are linked to obesity risk. Some affect appetite, others affect how fat is stored or how efficiently energy is burned. Rare mutations in genes like LEPR or POMC cause severe early-onset obesity, but even common gene variations make some people more prone to weight gain in today’s food environment. Genetics doesn’t mean destiny-but it does mean some people need more support to manage their weight.

Why do women gain weight after menopause?

Estrogen helps regulate fat distribution and energy use. After menopause, estrogen drops, leading to increased appetite, reduced metabolism, and more fat stored around the abdomen. Studies show women can gain 12-15% more belly fat in just five years after menopause. This isn’t just aging-it’s hormonal. Hormone replacement therapy may help some, but weight management still requires addressing appetite signals and metabolic changes.

Is obesity the same as being overweight?

No. Overweight means a BMI between 25-29.9. Obesity is a BMI of 30 or higher-and it’s a disease. People with obesity have biological changes that affect appetite, metabolism, and fat storage. Many overweight people don’t have these dysfunctions. Obesity carries higher risks for diabetes, heart disease, and cancer. Treating obesity requires more than just losing a few pounds-it requires fixing the underlying physiology.

Comments (9)

Evelyn Shaller-Auslander

November 28, 2025 AT 23:30

this made me cry. i thought i was just lazy, but turns out my brain was just broken. thank you for explaining it like i’m not a failure.

Gus Fosarolli

November 29, 2025 AT 20:59

so let me get this straight-my body’s got a broken smoke alarm, a stuck thermostat, and a greedy toddler screaming for snacks in my hypothalamus? 🤦♂️

and they call it ‘lack of willpower’? lol. i’d rather fight a dragon than my own biology.

Nirmal Jaysval

December 1, 2025 AT 05:09

u guys r so soft. back in my village in india, we just ate less n walked more. no drugs. no excuses. u just need discipline. stop blaming hormones.

Emily Rose

December 1, 2025 AT 08:11

NO. JUST NO. This isn’t about discipline, it’s about neurobiology. Nirmal, you’re repeating the same harmful myth that’s been killing people for decades. We don’t shame diabetics for needing insulin-we shouldn’t shame people with obesity for needing meds that fix their broken signals. This is medicine, not morality.

Benedict Dy

December 2, 2025 AT 01:46

While the biological mechanisms described are well-documented, the article overlooks the confounding influence of socioeconomic factors. Access to nutrient-dense foods, safe spaces for exercise, and healthcare literacy remain critical variables. Reducing obesity to neuroendocrine dysfunction alone risks medicalizing a problem rooted in systemic inequality.

John Power

December 2, 2025 AT 22:25

bro this is the most accurate thing i’ve ever read about why i can’t lose weight. i lost 40 lbs once, felt amazing… then my body turned into a traitor. i was starving all the time, felt like i was running through molasses. i thought i was weak. turns out my brain was just screaming ‘FIRE!’ when there was no smoke. 🙏

semaglutide changed my life. not a magic pill, but it finally let me breathe.

Scott McKenzie

December 4, 2025 AT 00:01

OMG YES 😭

Leptin resistance is REAL. I didn’t know my body was lying to me. I thought I was just ‘bad at dieting’… turns out my fat cells were screaming and my brain was wearing noise-canceling headphones. 🤯

Just started on GLP-1 meds. First week: no 3am ice cream cravings. I’m crying happy tears. Thank you for writing this.

Jeremy Mattocks

December 4, 2025 AT 01:23

Let me expand on something the article barely touched on-the epigenetic component. Chronic stress, poor sleep, and even childhood trauma can alter gene expression related to appetite regulation and fat storage. It’s not just about what’s happening now-it’s about what your body learned over years of survival mode. Cortisol doesn’t just make you crave sugar; it rewires your hypothalamus to prioritize energy conservation, even if you’re not under threat anymore. That’s why people who’ve been dieting for decades often feel like they’re fighting a ghost. It’s not their fault. It’s their biology carrying the scars of past survival strategies. And that’s why long-term treatment needs to include trauma-informed care, sleep hygiene, and stress management-not just pills. The body remembers. We have to help it forget.

Paul Baker

December 4, 2025 AT 20:24

this is why i stopped hating myself. i thought i was weak but turns out my brain is just glitchy. thx for the science not the shame 🙏❤️