Every year, tens of thousands of children end up in emergency rooms because of a simple mistake: the wrong dose of medicine. Not because parents are careless. Not because doctors are negligent. But because the system is built for adults, and kids don’t fit.

One mother gave her 10-kilogram toddler 5 milliliters of liquid acetaminophen, thinking it was the right amount. She didn’t realize the label meant 5 milligrams per kilogram. That’s a tenfold overdose. The child was rushed to the ER. This isn’t rare. It happens more than you think.

Why Pediatric Medication Errors Happen

Pediatric medication errors are more common than adult ones-31% of all medication events in kids’ emergency departments involve mistakes, compared to just 13% in adults. Why? Because kids aren’t small adults. Their bodies process drugs differently. Their doses are calculated by weight, not fixed numbers. One wrong decimal point can mean the difference between healing and harm.

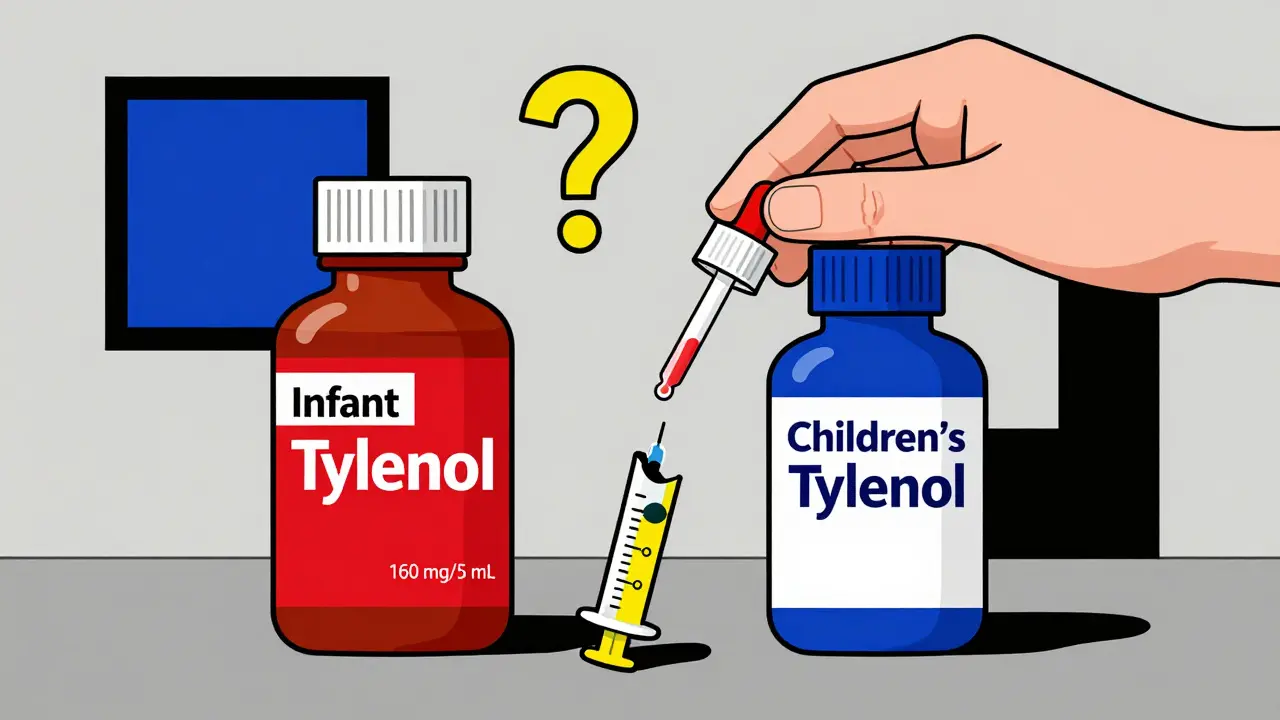

Most errors come from three places: calculation mistakes, misreading labels, and using the wrong measuring tool. A study in JAMA Network Open found that 60 to 80% of dosing errors at home involve liquid medications. Parents often use kitchen spoons, cups, or even droppers not meant for medicine. One parent on Reddit shared how they gave their 2-year-old children’s Tylenol instead of infant concentrate-two different concentrations-and didn’t realize until the pediatrician called back.

Weight measurement errors are another silent killer. In 10 to 31% of cases, the child’s weight is recorded incorrectly. A child weighing 15 kg might be listed as 15 lbs. That’s a 70% overdose right there. And in high-pressure emergency rooms, with multiple caregivers, verbal orders, and tired staff, these mistakes slip through.

The Hidden Costs of a Single Mistake

It’s not just about the immediate danger. Medication errors in children cost the U.S. healthcare system an estimated $28 million a year in emergency visits alone. About 13% of these errors cause actual harm-vomiting, liver damage, seizures. Another 47% reach the child but cause no harm. And 30% are caught before they ever reach the child. Those are the near misses. The ones we never hear about.

But the real tragedy? Many of these errors are preventable. And they’re not just happening in hospitals. A 2023 study in Pediatrics found that 40% of children with chronic illnesses-like asthma, epilepsy, or cancer-experience dosing errors at home. One in ten parents of children with leukemia mismeasure chemotherapy doses. That’s not a failure of love. It’s a failure of design.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Not all families face the same risks. Those with limited health literacy are 2.3 times more likely to make a dosing error. Families who speak limited English have error rates of 45%, compared to 28% for English-speaking families. Medicaid-enrolled children face 27% higher error rates than those with private insurance. These aren’t random. They’re tied to access, education, and systemic gaps.

And here’s the kicker: most hospitals don’t track these errors well. Only 10 to 30% of mistakes are reported through official channels. A 2004 study found that when researchers analyzed syringe concentrations in pediatric ERs, they found errors that had never been documented. That means the official numbers are hiding a much bigger problem.

What’s Working: Real Solutions from the Front Lines

Some hospitals are fixing this. Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, slashed harmful medication events by 85% over five years. How? They didn’t just train staff. They redesigned the whole system.

They made every pediatric dose in the emergency room go through a pharmacy check before it’s given. They built weight-based dosing calculators directly into their electronic records. They started using double-checks for high-risk drugs like epinephrine and insulin. And they trained every nurse, doctor, and tech in pediatric-specific medication safety-four to six hours of training, then quarterly refreshers.

At the same time, a program called MEDS (Medication Error Reduction in the ED) tested a simple idea: give parents clear, picture-based instructions and ask them to repeat the dose back. Just 90 seconds extra per patient. The result? Dosing errors dropped from 64.7% to 49.2%. Even after the program ended, the rate stayed 8% lower than before. That’s lasting change.

What Parents Can Do Right Now

You don’t need to wait for the hospital to fix things. Here’s what works, based on real data:

- Use only the tool that comes with the medicine. Not a teaspoon. Not a shot glass. The syringe or cup that came in the box. If it’s missing, call the pharmacy for a new one.

- Always check the concentration. Infant Tylenol is 160 mg/5 mL. Children’s Tylenol is 160 mg/5 mL too-but some brands differ. If you’re unsure, ask the pharmacist to write it on the bottle.

- Write down the dose. Weight in kg? Dose in mg/kg? Total mg? Write it on your phone or a sticky note. Don’t rely on memory.

- Ask the teach-back question. When the nurse gives you instructions, say: “Can you please have me repeat it back?” If they say no, push for it. It’s a safety standard for a reason.

- Keep a medication log. Write down what you gave, when, and why. This helps avoid double dosing. Especially at night, when you’re tired.

One parent told me she kept a small notebook in her diaper bag. Every time she gave medicine, she checked it off. “It stopped me from giving Tylenol twice in four hours,” she said. “I didn’t even realize I was doing it until I saw it on paper.”

The Bigger Picture: Why This Isn’t Just a Parent Problem

It’s easy to blame parents. But the real issue is that the system was never built for kids. Adult hospitals use fixed doses. Pediatric hospitals need custom calculations. Most community ERs don’t have pediatric-specific EMRs. They use the same software as for adults. No weight-based alerts. No built-in safety checks.

Only 68% of children’s hospitals have automated dosing calculators in their systems. That means one in three ERs treating kids are flying blind. And in places with fewer resources-rural clinics, safety-net hospitals-there’s often no pharmacist on site to double-check. That’s not negligence. It’s inequality.

The American Academy of Pediatrics says medication safety is one of their top five priorities. They’re pushing for standardized metrics to track outpatient errors by 2025. That’s progress. But until every ER, every pharmacy, every home has the same tools, the same training, the same safety nets, children will keep paying the price.

What Needs to Change

Here’s what real change looks like:

- Universal pediatric EMR design. All emergency department software must include weight-based dosing alerts and concentration warnings.

- Standardized liquid formulations. All children’s acetaminophen and ibuprofen should be the same concentration nationwide. No more guessing.

- Pharmacy-led discharge checks. Every child leaving the ER with a new prescription should get a 2-minute phone call from a pharmacist to confirm the dose.

- Free measuring tools. Every prescription for liquid medicine should come with a calibrated syringe. No exceptions.

- Language-accessible instructions. All discharge papers must be available in the family’s primary language-with pictures, not just words.

These aren’t expensive fixes. They’re smart ones. And they’ve already worked in places that tried them.

Final Thought: Safety Is a Team Sport

Medication safety isn’t about being perfect. It’s about building layers of protection. A doctor checks the weight. A nurse verifies the dose. A pharmacist confirms the concentration. A parent uses the right syringe. And a system that remembers to warn you when something’s off.

One child’s life doesn’t need a miracle. It just needs a system that doesn’t fail them.

Comments (9)

Maggie Noe

January 8, 2026 AT 20:58

This hit me right in the feels. I gave my 18-month-old the wrong concentration of Tylenol once-just a tiny mix-up between infant and children’s-and spent 48 hours in a panic. She was fine, thank God, but I’ll never forget the way my hands shook holding that syringe. We need better labels. Like, seriously. Why does medicine have to be a puzzle? 🤕💔

Catherine Scutt

January 9, 2026 AT 11:33

Of course parents mess up. But the real problem? Hospitals still use adult EMRs for kids. No weight alerts. No concentration warnings. It’s not negligence-it’s laziness. And the fact that only 10-30% of errors get reported? That’s not data. That’s cover-up.

Gregory Clayton

January 10, 2026 AT 03:58

Y’all are overcomplicating this. Just use the damn syringe that comes with the bottle. No one’s asking you to be a pharmacist. Stop blaming the system and start paying attention. My kid’s never had a dosing error because I don’t trust my memory. I write it down. I use the tool. Done.

Jeffrey Hu

January 10, 2026 AT 07:57

Actually, the JAMA study you cited only looked at outpatient errors-hospital errors are even worse. And you missed that 72% of dosing mistakes happen in the first 24 hours after discharge. That’s when parents are exhausted, confused, and handed a stack of papers in 8-point font. Also, ibuprofen concentrations vary by brand in the U.S. but are standardized in Canada. We’re behind. Way behind.

Drew Pearlman

January 10, 2026 AT 11:11

I’m so glad someone finally said this out loud. My daughter has epilepsy and we’ve had three near-misses in two years. Once I gave her 15mg instead of 150mg because the pharmacy printed the label wrong and I didn’t catch it. I cried for an hour. But here’s the thing-every time I’ve asked for a pharmacist to call me after discharge, they’ve said ‘we don’t have the bandwidth.’ That’s not acceptable. We need a national standard. Not just for kids with chronic illness-every kid. Every single time. It’s not a luxury. It’s survival.

Johanna Baxter

January 11, 2026 AT 14:07

They’re not even trying. I work in a rural ER. We don’t have a pediatric pharmacist. We don’t have weight-based alerts. We use the same EMR as the adult floor. I’ve seen a 12-pound baby get a 12-kilo dose. And the worst part? No one even blinked. We’re not failing parents-we’re failing children. And nobody’s getting fired for it.

Elisha Muwanga

January 12, 2026 AT 06:05

Let’s be honest-this isn’t a systemic failure. It’s a cultural one. People don’t read labels. They don’t ask questions. They assume. And now we’re going to force pharmacies and hospitals to redesign everything because parents won’t take basic responsibility? Maybe if we stopped treating them like fragile children, they’d start acting like adults.

Jerian Lewis

January 14, 2026 AT 01:46

That study from Pediatrics? I read it. The real takeaway isn’t that parents are bad-it’s that we’ve normalized dangerous practices. Using kitchen spoons? That’s not ignorance. That’s institutional abandonment. And the fact that we still don’t have a national standard for liquid concentrations? That’s a moral failure.

Kiruthiga Udayakumar

January 15, 2026 AT 16:14

My cousin in India gave her baby the wrong dose because the bottle had no English label. No pictures. No instructions. Just a tiny print in Hindi. She didn’t know. No one told her. We need global standards. Not just in the U.S. This isn’t about money. It’s about dignity.