When you buy a generic pill in Germany, France, or Spain, its price isn’t just decided by the manufacturer or local market demand. It’s often pulled from a list of prices in other countries. This is called international reference pricing - and it’s how most of Europe keeps generic drug costs low. But how exactly does it work? And why do some countries see shortages while others save billions?

What Is International Reference Pricing?

International reference pricing (IRP), also known as external reference pricing, is when a country looks at what other nations charge for the same generic medicine and uses that to set its own price. It’s not about what the drug costs to make - it’s about what others are paying. This system became common in the 1980s, starting with Italy, Spain, and Portugal, as governments tried to stop pharmaceutical spending from ballooning.Today, 34 out of 38 high-income countries use some version of IRP. But for generic drugs, it’s not just about comparing prices across borders. Most European countries use something called internal reference pricing instead. That means they group together all generic drugs that treat the same condition - like all versions of metformin for diabetes - and set one reimbursement price based on the cheapest one in the group. Any drug in that group that costs more gets less coverage. Patients might still buy it, but they pay the difference.

How Countries Choose Which Prices to Reference

Not every country looks at the same set of reference nations. Western European countries typically compare prices from France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK. Eastern European countries often use Austria, Germany, and the Netherlands. The choice matters. If you pick countries with very low prices, your own prices will drop fast - sometimes too fast.Most countries calculate the reference price using the median or average of their reference basket, not the lowest price. Why? Because if you base your price on the cheapest drug in the world, you risk making it impossible for manufacturers to stay in business. The European Federation of Pharmaceutical Industries and Associations (EFPIA) recommends this approach for fairness and predictability.

Some countries tweak the formula. Switzerland, for example, sets generic prices at two-thirds of the average international price and one-third based on its own domestic prices. That way, it doesn’t get dragged down by the lowest-cost countries but still benefits from lower prices than its neighbors.

Internal vs. External Reference Pricing for Generics

There’s a big difference between how IRP works for brand-name drugs versus generics. For patented drugs, countries often use external reference pricing - comparing prices across borders directly. For generics, most use internal reference pricing.Why? Because generics are interchangeable. A 500mg metformin tablet from one maker works just like another. So instead of comparing prices between countries, regulators group similar drugs together and cap the price at the lowest cost in the group. Germany’s AMNOG system, for example, reimburses all drugs in a therapeutic group at the lowest price plus a 3% margin. That pushes manufacturers to compete on price, not marketing.

In the Netherlands, it’s even more aggressive. They combine internal reference pricing with mandatory discounts and tendering. As a result, generic prices are 65-85% lower than the original brand drugs. That’s one reason why generic use in the Netherlands is over 90% - the highest in Europe.

What Happens When Prices Drop Too Low?

Lower prices sound great - until patients can’t find the medicine. Greece is a cautionary tale. During its financial crisis (2010-2018), the government slashed generic drug prices using IRP, updating them every quarter. Prices fell by over 40% in some cases. But manufacturers couldn’t make a profit. By 2015, 37% of generic medicines experienced shortages. Pharmacies had to substitute other brands, and patients sometimes waited days for their prescriptions.Portugal saw the same thing. In 2019, 22 generic products disappeared from the market because the prices set by IRP didn’t cover production costs. This isn’t just about big companies leaving - it’s about small manufacturers who can’t absorb the losses. As Simon-Kucher & Partners warned, strict IRP without considering manufacturing costs leads to market exit.

Even in countries without shortages, there’s a trade-off. A 2019 study found that countries relying solely on IRP for generics saw 22% greater price reductions - but also 18% longer delays in bringing new generic versions to market. Manufacturers wait to launch because they know prices will be capped low from day one.

How the U.S. and Canada Handle Generic Prices

The United States doesn’t use international reference pricing for generics in federal programs like Medicare or Medicaid. Instead, prices are driven by competition, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), and bulk purchasing. But some states are experimenting. Colorado’s Medicaid program started using reference pricing for generics in 2021, and it saved 12-15% on drug costs, according to CMS data.Canada takes a different path. The federal Patented Medicine Prices Review Board (PMPRB) uses IRP for brand-name drugs - but not for generics. Generic prices are set by individual provinces through tendering. Ontario and Quebec hold competitive bids where manufacturers submit lowest-price offers. The province picks the winner and locks in the price for a year. This system gives provinces more control and avoids the pitfalls of international price dragging.

Who Benefits and Who Loses?

Patients in countries with strong IRP systems generally pay less. A 2021 OECD survey showed 78% of patients were satisfied with generic substitution under IRP. But 34% worried the cheaper versions weren’t as good - even though there’s no clinical difference.Pharmacists see the effects daily. In Spain, internal reference pricing increased generic substitution from 52% in 2010 to 89% today. But 63% of pharmacists reported occasional shortages of the lowest-priced brand, forcing them to switch patients to alternatives - sometimes without their consent.

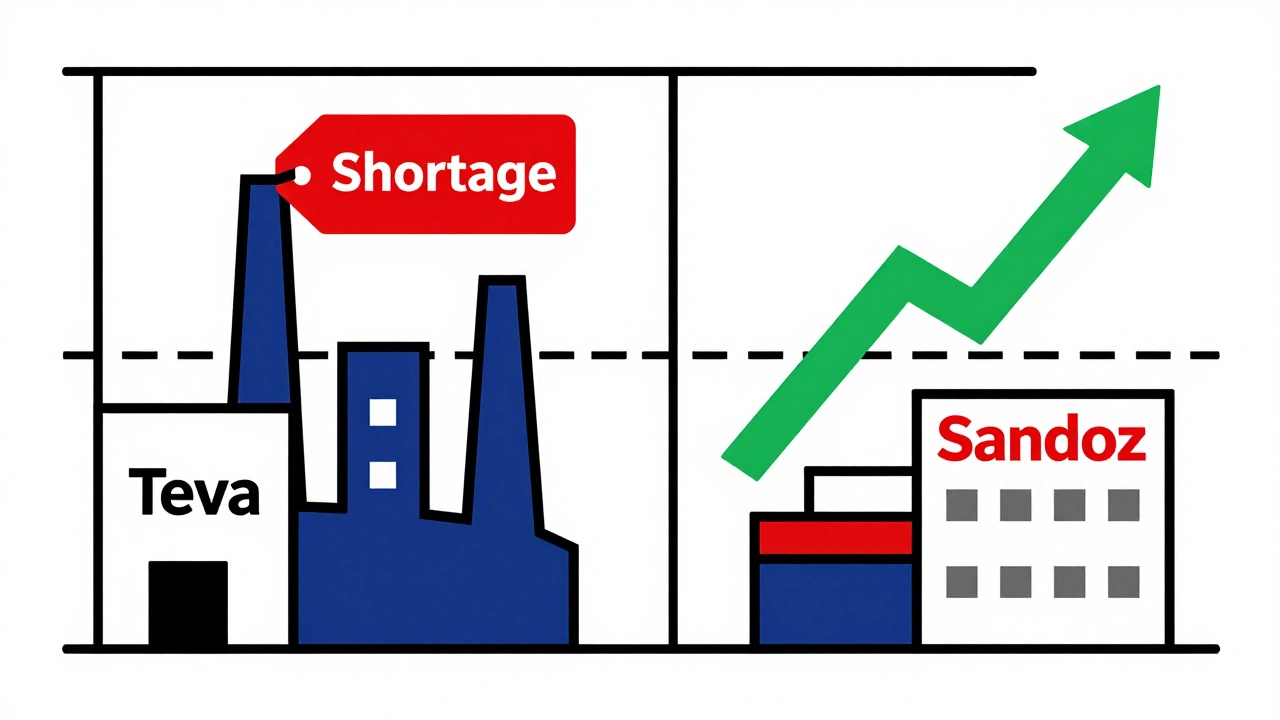

Manufacturers are caught in the middle. Teva reported a 9% revenue decline in its European generics division between 2020 and 2022, even though sales volume grew by 15%. Sandoz, on the other hand, said well-designed IRP helped them expand in 18 countries. The difference? Companies that invested in cost-efficient production and high-quality manufacturing did better.

Hospitals benefit too. Germany’s internal reference system reduced administrative burden by 37%, because procurement teams didn’t have to negotiate dozens of individual prices. They just bought from the approved list.

The Future of Generic Drug Pricing

IRP isn’t going away - it’s getting smarter. France launched a new system in January 2023 called dynamic reference pricing. Instead of setting prices once a year, it adjusts them quarterly based on which generic brands are selling the most. If a cheaper version suddenly dominates the market, its price gets pulled down further. Early results show an extra 8.2% savings.The European Commission is testing a European Reference Pricing Platform, launched in April 2023. It’s a pilot that shares pricing data across seven countries for 15 generic medicines. If it works, it could expand to 100 drugs by 2025. The goal? More transparency, fewer surprises, and smarter price setting.

But experts warn that current systems aren’t ready for complex generics - drugs like inhalers, injectables, or biosimilars that cost nearly as much to develop as brand-name drugs. A 2023 RAND Corporation study found that strict IRP discourages investment in these products. The OECD now recommends tiered reference groups: simple generics get the lowest prices, complex ones get higher, fairer rates.

What Works Best?

Professor Panos Kanavos from the London School of Economics found that countries using 5-7 reference countries got the best balance: average price reductions of 28% with 97% drug availability. Countries using more than 10 saw diminishing returns - only 31% price drop, but 12% higher shortage rates.Here’s what successful IRP systems have in common:

- They use internal reference pricing, not just external comparisons.

- They set reference prices based on median or average, not the lowest.

- They limit their reference basket to 5-7 similar countries.

- They update prices annually or semi-annually - not quarterly.

- They allow small margins for quality and manufacturing complexity.

When these rules are followed, IRP works. It lowers costs without breaking supply chains. When ignored, it leads to shortages, delays, and lost innovation.

What Patients and Providers Should Know

If you’re on a generic drug, your price might be lower because your country is comparing it to what France or Germany pays. That doesn’t mean the drug is less effective. In fact, most generics are identical in quality to brand-name versions.But if your pharmacy says your usual brand is out of stock - and the replacement is cheaper - it’s likely because of IRP. You have the right to ask for your original brand, but you may pay more out of pocket.

For prescribers, understanding IRP helps you choose wisely. In countries with mandatory substitution rules, you may be required to prescribe the lowest-priced option if the price difference exceeds 20%. That’s not about cost-cutting - it’s about system design.

For policymakers, the lesson is clear: IRP is powerful, but it’s not a magic button. It needs careful design, monitoring, and flexibility. Otherwise, the savings come at the cost of access.

What is international reference pricing for generic drugs?

International reference pricing (IRP) is when a country sets the price of generic drugs by looking at what other countries pay for the same medicine. Instead of letting manufacturers set prices freely, governments use prices from a group of similar countries - like France, Germany, or Spain - to determine how much they’ll reimburse for each generic drug.

Do all countries use the same countries as references?

No. Western European countries usually compare prices from France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK. Eastern European countries often use Austria, Germany, and the Netherlands. Some countries, like Switzerland, mix international prices with their own domestic prices to avoid being dragged down by very low-cost nations.

Why do some countries have generic drug shortages?

When IRP sets prices too low, manufacturers can’t cover production costs. This happened in Greece during its financial crisis, where 37% of generic drugs faced shortages. Companies stopped making or importing drugs that didn’t make a profit, even if they were needed.

Is internal reference pricing better than external reference pricing for generics?

Yes, for generics. Internal reference pricing groups similar drugs together and sets one reimbursement price based on the lowest cost in the group. This encourages competition among manufacturers of the same drug. External reference pricing, which compares prices across countries, is more common for brand-name drugs and can cause unpredictable price drops for generics.

Does the U.S. use international reference pricing for generics?

No, not at the federal level. U.S. generic prices are set by market competition, pharmacy benefit managers, and bulk purchasing. But some states, like Colorado, have started using limited reference pricing for Medicaid generics, saving 12-15% on those drugs.

What’s the biggest risk of using international reference pricing?

The biggest risk is the "pricing spiral" - when one country lowers its price, others follow, pushing prices down further. This can make it impossible for manufacturers to stay profitable, leading to shortages, delayed market entry for new generics, and reduced investment in complex generic drugs like inhalers or injectables.

How do countries avoid the downsides of IRP?

Successful countries limit their reference basket to 5-7 similar nations, use median or average prices (not the lowest), update prices annually, and allow small margins for manufacturing complexity. They also monitor supply chains closely and adjust rules if shortages appear.

Next Steps for Policymakers and Patients

If you’re a policymaker, start with a small pilot. Pick one therapeutic group - like statins or antibiotics - and test internal reference pricing with a 5-country basket. Track shortages, substitution rates, and manufacturer responses. Don’t rush to apply it to all generics.If you’re a patient, know your rights. If your pharmacy switches your generic brand, ask why. If you’re concerned about quality, talk to your doctor. Most generics are just as safe and effective - but you deserve to know what’s being substituted.

For manufacturers, the message is simple: adapt or exit. If you’re in a country with strict IRP, focus on efficiency, quality, and cost control. If you make complex generics, push for tiered pricing systems that recognize your higher costs. The future of generics isn’t about the lowest price - it’s about sustainable access.

Comments (16)

Shannara Jenkins

December 3, 2025 AT 13:07

Love how this breaks down IRP without the usual jargon. I work in pharmacy and see the shortages firsthand - it’s wild how a 10% price cut can make a drug vanish overnight. Glad someone’s talking about the human side, not just the numbers.

Elizabeth Grace

December 5, 2025 AT 07:42

Ugh I swear every time my prescription switches to a new generic I feel like I’m playing Russian roulette with my meds. Like yeah it’s ‘the same’ but my anxiety went through the roof when they swapped my metformin and I swear I felt weird for a week. Who even tested this?!

Steve Enck

December 6, 2025 AT 03:01

The structural fallacy in IRP lies in its ontological assumption that price equates to value - a neoliberal delusion rooted in utilitarian economics. When manufacturers are forced into a race to the bottom, they do not optimize for quality or innovation; they optimize for survival. This is not policy - it is market cannibalism disguised as fiscal responsibility.

मनोज कुमार

December 6, 2025 AT 10:58

IRP works if you dont overdo it. Greece fucked up by cutting prices every quarter. Simple fix: median of 5 countries annual update. Done.

Joel Deang

December 7, 2025 AT 00:00

omg this is so cool!! i had no idea other countries did this 😍 i live in colorado and they just started doing it and my dad’s blood pressure med went from $45 to $8!! like?? how is that even fair?? 🤯

Roger Leiton

December 7, 2025 AT 13:45

This is actually one of the most well-researched pieces I’ve read on drug pricing. I’m really curious - if the EU is testing a shared platform, do you think the U.S. could ever join something like that? Or would the PBMs kill it before it even starts? 🤔

Laura Baur

December 8, 2025 AT 15:31

Let’s be honest - this whole system is a facade of efficiency. The real issue isn’t pricing, it’s the moral bankruptcy of treating life-saving medication like a commodity. You can’t reduce human health to a spreadsheet. The fact that we even debate whether a 3% margin is ‘fair’ for insulin or metformin reveals the rot at the core of our healthcare philosophy. People are dying because someone in a boardroom decided that ‘median price’ is more important than ‘availability.’

And don’t get me started on the false equivalence between ‘generic’ and ‘identical.’ The excipients vary. The dissolution rates vary. The bioavailability varies. And yet we pretend it’s all the same because the FDA says so. That’s not science - it’s corporate propaganda dressed in white coats.

If you think IRP is just about cost savings, you’re not paying attention. It’s about control. Who controls the supply? Who controls the narrative? Who controls whether you live or wait? This isn’t policy. It’s social engineering with a side of pharmaceutical capitalism.

And yes, I’ve read the OECD reports. I’ve read the RAND studies. I’ve read the EFPIA white papers. They all say the same thing: ‘It works if you do it right.’ But ‘right’ is defined by who has the power to define it. And right now, that’s not you. It’s not me. It’s not the patient. It’s the regulator with a spreadsheet and a 401(k).

So go ahead and pat yourselves on the back for your 28% savings. Just remember - behind every dollar saved is a pharmacy shelf with an empty space where your child’s medicine used to be.

Jack Dao

December 9, 2025 AT 22:58

Wow. So we’re just supposed to trust that ‘internal reference pricing’ means the pills are the same? What’s next? ‘All bread is bread’ so let’s just feed everyone store-brand Wonder Bread and call it nutrition? 🤡

Also - who’s paying for the lawsuits when someone has a bad reaction to a ‘substituted’ generic? Not the state. Not the pharmacist. Always the patient.

dave nevogt

December 10, 2025 AT 12:41

I’ve spent years working in rural clinics where the only thing standing between a diabetic and blindness is a $2 generic. I’ve seen people cry because their insurance wouldn’t cover the brand, and the cheapest generic was out of stock. I’ve held hands while they waited three days for a refill.

IRP isn’t perfect. But in places where there’s no safety net, it’s the only thing keeping people alive. The problem isn’t the system - it’s that we only fix it when people die. We wait for Greece. We wait for Portugal. We wait until the shelves are empty.

What if we stopped waiting? What if we designed IRP not to save money, but to save lives? That’s the question no one asks. Because saving lives is harder than saving dollars.

Arun kumar

December 11, 2025 AT 06:01

india does this diffrently. we dont use intenational price. we set price based on cost of production + 10%. no shortage. no drama. simple.

Zed theMartian

December 12, 2025 AT 17:21

Oh wow. So you’re telling me that Europe - the land of free healthcare and unicorn unicorns - is actually just a giant price-fixing cartel? And we’re supposed to admire this? What’s next? The WHO setting the price of oxygen? Maybe the UN will start regulating how much water you can drink per day based on what’s affordable in Iceland.

Let me guess - next they’ll make you pay extra if your generic pill is ‘too effective.’

Ella van Rij

December 14, 2025 AT 15:17

So let me get this straight - we’re supposed to be impressed that a country can cut drug prices by 65%… by making manufacturers go bankrupt? That’s not innovation. That’s just… theft with a spreadsheet. 🙄

Also, ‘dynamic reference pricing’? Sounds like a Netflix algorithm for your medicine. ‘You watched metformin. You liked metformin. Here’s a cheaper version that might kill you.’

ATUL BHARDWAJ

December 15, 2025 AT 00:53

India makes 40% of global generics. We dont need to reference anyone. We set price based on cost. No shortage. No crisis. Simple math.

Steve World Shopping

December 15, 2025 AT 18:21

IRP is just neoliberalism in a lab coat. The real issue is commodification of life. The pharmaceutical-industrial complex thrives on scarcity and control. IRP is a Band-Aid on a hemorrhage. Until we dismantle the patent regime and nationalize production, we’re just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

Rebecca M.

December 17, 2025 AT 09:20

Oh honey. You mean to tell me that when my pharmacist hands me a pill I’ve never seen before and says ‘it’s the same!’ - it’s actually because some bureaucrat in Berlin decided my metformin should cost 3 euros? And I’m supposed to be grateful? 😭

My insurance doesn’t care. My doctor doesn’t care. But my body remembers the difference. And now I’m on a new antidepressant because the ‘generic’ made me feel like a zombie.

Who’s gonna pay for my therapy?

Shannara Jenkins

December 18, 2025 AT 02:19

Rebecca M. - I feel you. I had the same thing happen with my thyroid med. Switched to a ‘same’ generic and my TSH went haywire. Took three months to get back to normal. Pharmacies need to track batch effects - not just price points.

Also - Arun Kumar? You’re right. India’s model is the outlier that actually works. Maybe we should look at how they do it, not just how Europe messes it up.