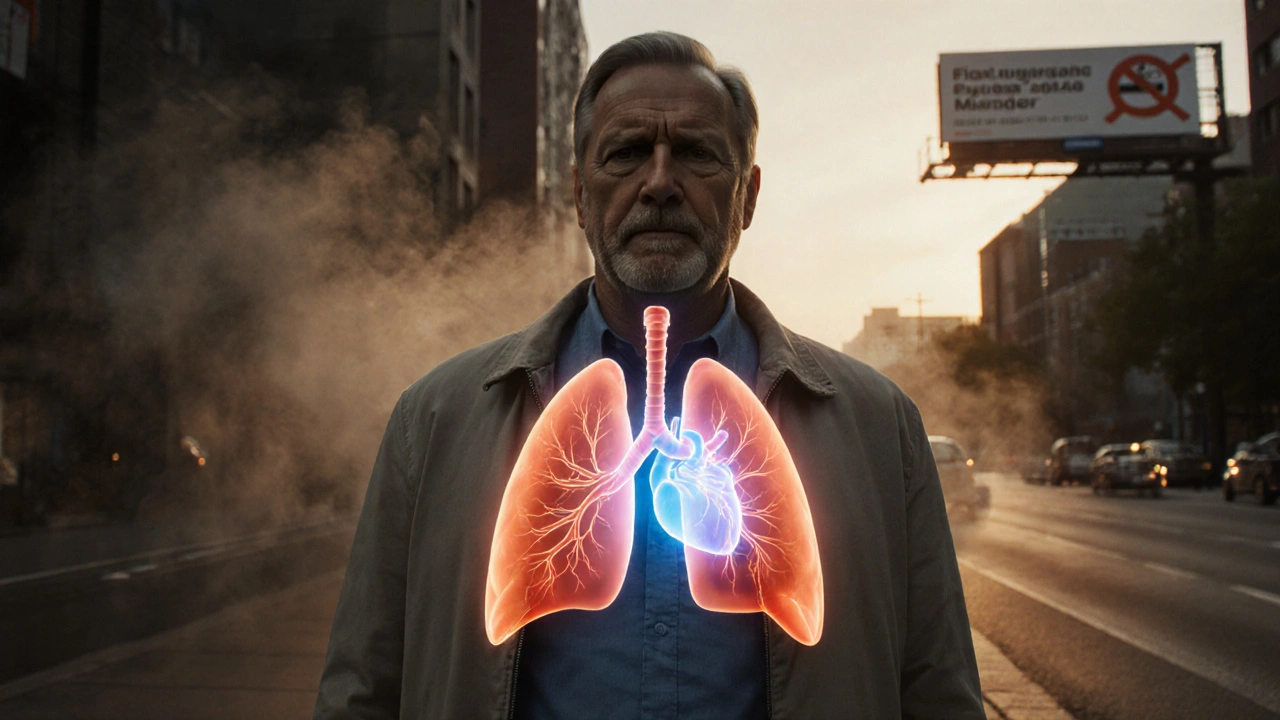

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is a progressive obstructive lung disorder characterized by airflow limitation that is not fully reversible. It affects roughly 16 million adults in the United States and is the third leading cause of death worldwide (World Health Organization, 2023). The disease stems mainly from long‑term exposure to harmful particles, most often cigarette smoke.

Heart Disease (also called cardiovascular disease) encompasses conditions that impair the heart’s ability to pump blood, including coronary artery disease, heart failure, and arrhythmias. In the U.S., about 18 million adults live with some form of heart disease (American Heart Association, 2024).

The overlap between COPD and heart disease isn’t a coincidence. Researchers estimate that individuals with COPD have a 2-3‑fold higher risk of developing cardiovascular events than those with healthy lungs. Below, we unpack why the two illnesses are tangled, how clinicians spot the crossover, and what patients can do to lower their combined risk.

Why the Lungs and Heart Talk to Each Other

Three core mechanisms explain the connection:

- Systemic Inflammation: COPD triggers chronic release of inflammatory mediators such as C‑reactive protein (CRP), interleukin‑6 (IL‑6), and tumor necrosis factor‑α. These molecules circulate in the blood, accelerating atherosclerotic plaque formation in coronary arteries.

- Systemic Hypoxia: Damaged airways reduce oxygen exchange, leading to persistently low blood‑oxygen levels. The heart compensates by pumping faster and thicker muscle fibers develop, eventually straining the right ventricle.

- Pulmonary Hypertension: Elevated pressure in the lung’s blood vessels (pulmonary arterial pressure > 25mmHg at rest) forces the right side of the heart to work harder, a condition known as cor pulmonale.

Each pathway feeds the others, creating a vicious cycle that speeds up both lung and heart decline.

Key Shared Risk Factors

Understanding common triggers helps clinicians target prevention early. The table below compares the major risk drivers for COPD and heart disease.

| Risk Factor | COPD | Heart Disease |

|---|---|---|

| Smoking | Primary cause (≈85% of cases) | Major contributor (≈30% of cases) |

| Age | Incidence rises sharply after 55 | Risk doubles every decade after 45 |

| Air Pollution | Long‑term exposure adds 10-15% risk | Fine particulate matter (PM2.5) linked to myocardial infarction |

| Obesity | Worsens dyspnea and inflammation | Elevates blood pressure, LDL, and glucose |

| Genetics | Alpha‑1 antitrypsin deficiency | Familial hypercholesterolemia |

Smoking stands out as the single most modifiable factor. Quitting reduces COPD progression and cuts cardiovascular mortality by about 30% within five years (U.S. Surgeon General, 2022).

Diagnosing the Overlap

When a patient with known COPD complains of new chest pain, palpitations, or swelling in the legs, clinicians must evaluate for cardiac involvement. The two most useful tools are:

- Spirometry is a pulmonary function test that measures the volume of air a person can exhale forcefully (FEV1) and the total lung capacity (FVC). A post‑bronchodilator ratio < 0.70 confirms airflow obstruction and helps stage COPD severity.

- Echocardiography uses ultrasound to visualize heart structure and function. It can reveal right‑ventricular enlargement, estimate pulmonary artery pressure, and detect left‑sided coronary disease.

Additional labs such as BNP (brain natriuretic peptide) for heart‑failure screening and high‑sensitivity CRP for inflammation provide a fuller picture. A combined approach-lung function, cardiac imaging, and biomarker profiling-yields the highest diagnostic accuracy.

How COPD Accelerates Specific Heart Conditions

Below we walk through the most common cardiovascular complications seen in COPD patients.

Cor Pulmonale (Right‑Heart Failure)

Persistent pulmonary hypertension raises the afterload on the right ventricle. Over time, the right ventricle hypertrophies, then dilates, leading to fluid‑back up in the liver, abdomen, and lower limbs. About 20% of severe COPD patients develop cor pulmonale (European Respiratory Society, 2021).

Atherosclerosis and Coronary Artery Disease

Systemic inflammation and oxidative stress damage the endothelium, promoting plaque formation. COPD patients often have higher LDL‑cholesterol levels and lower HDL‑cholesterol, compounding the risk.

Arrhythmias

Hypoxia and electrolyte shifts can trigger atrial fibrillation or ventricular ectopy. Studies show a 30% higher incidence of atrial fibrillation in COPD cohorts, especially during acute exacerbations.

Therapeutic Strategies that Hit Both Targets

Treatment must address lung pathology while protecting the heart. The following interventions have the strongest evidence.

Smoking Cessation Programs

Behavioral counseling combined with pharmacotherapy (varenicline or nicotine‑replacement) yields quit rates of 30-45% in COPD populations. The cardiovascular payoff is immediate-heart‑rate variability improves within weeks.

Bronchodilators and Inhaled Steroids

Long‑acting beta‑agonists (LABA) and anticholinergics improve airflow, reduce hyperinflation, and lower right‑ventricular afterload. Inhaled corticosteroids lessen airway inflammation, indirectly smoothing systemic inflammatory markers.

Cardiovascular Medications

- Statins: Beyond lowering LDL, statins have anti‑inflammatory properties that may slow COPD progression. A 2022 meta‑analysis found an 18% reduction in COPD exacerbations among statin users.

- Beta‑Blockers: Historically avoided due to bronchospasm risk, cardio‑selective beta‑blockers (e.g., bisoprolol) are now considered safe and improve survival in COPD patients with heart failure.

- ACE Inhibitors/ARBs: Help control blood pressure and improve endothelial function, lowering the burden of both diseases.

Exercise and Pulmonary Rehabilitation

Structured aerobic training raises VO₂max, improves skeletal‑muscle oxygen extraction, and reduces systemic inflammation. A 12‑week program can cut COPD hospitalization risk by 25% and improve left‑ventricular diastolic function.

Oxygen Therapy

Long‑term supplemental oxygen for patients with resting PaO₂<55mmHg extends survival and reduces pulmonary‑vascular resistance, easing right‑heart strain.

Monitoring and Follow‑Up

Because the disease trajectory can shift quickly, regular review is essential.

- Spirometry every 6-12months to track lung‑function decline.

- Echocardiogram annually or sooner if symptoms worsen.

- Blood biomarkers (BNP, hs‑CRP) every 3-6months for early heart‑failure detection.

- Medication reconciliation to avoid drug‑drug interactions-especially inhaled anticholinergics with beta‑blockers.

Patient education is a cornerstone. Teaching people to recognize early signs-new shortness of breath at rest, ankle swelling, or sudden chest tightness-can prompt timely medical attention.

Future Directions: Integrated Care Models

Researchers are testing “cardiopulmonary clinics” where pulmonologists and cardiologists co‑manage high‑risk patients. Early data suggest a 15% reduction in combined hospitalizations when care is coordinated. Telehealth platforms that stream spirometry and home‑based ECGs are also emerging, giving clinicians real‑time data to tweak therapy before crises occur.

Take‑Away Checklist for Patients and Providers

| What | Why | How |

|---|---|---|

| Quit Smoking | Reduces both lung and heart damage | Enroll in cessation program; use varenicline |

| Annual Spirometry | Tracks COPD progression | Schedule at primary‑care or pulmonary clinic |

| Yearly Echo | Detects pulmonary hypertension early | Ask cardiologist for screening |

| Statin Therapy (if indicated) | Lowers cholesterol and inflammation | Discuss with doctor; monitor liver enzymes |

| Cardio‑selective Beta‑Blocker (if heart failure) | Improves survival without worsening airway | Start low dose; titrate carefully |

| Pulmonary Rehab | Boosts exercise tolerance, reduces hospital stays | Join local or virtual program 2‑3×/week |

| Home Oxygen (if PaO₂<55mmHg) | Decreases right‑heart strain | Prescribe through pulmonology |

By addressing both sides of the equation, patients can enjoy longer, more active lives.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can COPD cause a heart attack?

Yes. The chronic inflammation and hypoxia seen in COPD accelerate atherosclerosis, which can destabilize coronary plaques and trigger a myocardial infarction. Studies show a 1.5‑to‑2‑fold increase in heart‑attack risk for moderate‑to‑severe COPD patients.

Is it safe to take beta‑blockers if I have COPD?

Cardio‑selective beta‑blockers such as bisoprolol or nebivolol are generally safe for COPD patients. They preferentially block beta‑1 receptors in the heart while sparing beta‑2 receptors in the lungs. Always start at a low dose and monitor lung function.

What symptoms suggest my COPD is affecting my heart?

Look for swelling in the ankles or feet, unexplained fatigue, rapid or irregular heartbeats, and shortness of breath that worsens when lying flat (orthopnea). These signs often point to right‑ventricular strain or early heart failure.

How often should I get a chest X‑ray if I have both COPD and heart disease?

A baseline chest X‑ray is useful at diagnosis. After that, repeat imaging only if there’s a change in symptoms, such as new cough, increased wheezing, or signs of fluid overload. Routine annual X‑rays are not required.

Do inhaled steroids help protect the heart?

Inhaled corticosteroids primarily reduce airway inflammation, but they also lower systemic CRP levels, which can modestly reduce cardiovascular risk. The benefit is smaller than that of statins, but it adds to overall protection.

Comments (13)

Asia Lindsay

September 26, 2025 AT 22:45

Great summary! 👍 The link between COPD and heart disease is often overlooked, and this post really shines a light on it. Keep spreading the knowledge! 😊

Julian Macintyre

September 28, 2025 AT 02:32

While the exposition is largely accurate, one must admonish the author for an occasional paucity of mechanistic depth. The inflammatory cascade, for instance, could be delineated with greater specificity regarding cytokine signaling pathways. Moreover, the discussion of pulmonary hypertension omits the role of endothelin‑1, a notable vasoconstrictor. The omission, albeit minor, detracts from an otherwise comprehensive review. In sum, the article merits commendation, yet a more rigorous treatment of molecular underpinnings would elevate its scholarly merit.

Angela Marie Hessenius

September 29, 2025 AT 06:18

From a cultural perspective, the intertwining of respiratory and cardiac health reflects a broader narrative about how lifestyle, environment, and socioeconomic factors converge to shape disease patterns across the globe. In many developing nations, exposure to indoor biomass fuels mirrors the cigarette‑induced risk seen in the United States, underscoring the universality of the problem. Historically, the industrial revolution introduced a wave of air pollution that accelerated respiratory ailments, which in turn laid the groundwork for the modern epidemic of cardiovascular disease. The table presented in the article eloquently juxtaposes smoking, age, and pollution, yet it also hints at deeper societal inequities that influence access to care and preventive resources. For instance, urban dwellers may benefit from better emergency services, while rural patients often face delayed diagnoses, compounding the morbidity associated with COPD‑heart comorbidity. Moreover, the psychosocial stressors linked to chronic illness can precipitate hypertension through neuroendocrine pathways, further blurring the line between lung and heart pathology. It is also worth noting that genetic predispositions, such as alpha‑1 antitrypsin deficiency, interact with environmental triggers in a complex epistatic fashion, amplifying disease severity. The article’s emphasis on smoking cessation is crucial, yet public health initiatives must also address air quality standards, occupational exposures, and nutritional counseling to provide a holistic mitigation strategy. In rehabilitation settings, incorporating culturally tailored exercise programs can improve adherence among diverse populations, thereby enhancing both pulmonary function and cardiac output. Finally, the emerging role of statins as anti‑inflammatory agents offers a promising avenue for integrated therapy, though clinicians must remain vigilant about potential drug‑drug interactions, especially in polypharmacy contexts common among older adults. In conclusion, the intricate dance between the lungs and heart is a testament to the body’s interconnectedness, and it calls for multidisciplinary collaboration that respects both biomedical evidence and cultural nuance.

Patrick Hendrick

September 30, 2025 AT 10:05

Excellent points, very insightful, well‑written, and concise.

abhishek agarwal

October 1, 2025 AT 13:52

Look, the data are clear-quit smoking now or face a cascade of heart problems! No more excuses, just action.

gershwin mkhatshwa

October 2, 2025 AT 17:38

Interesting read. I’ve seen patients who swear by pulmonary rehab for both breathing and stamina. The cardio benefits are a real bonus.

tim jeurissen

October 3, 2025 AT 21:25

Correction: “statins have anti‑inflammatory properties” should be “statins possess anti‑inflammatory properties”.

lorna Rickwood

October 5, 2025 AT 01:12

life is fraught with paradoxes its strange how lung disease can pumoetntially sway the heart's beat while we breathe as if nothing is up

maybe that's why we need more awareness

Mayra Oto

October 6, 2025 AT 04:58

The article does a solid job of linking the two conditions. It also highlights actionable steps like smoking cessation and rehab.

S. Davidson

October 7, 2025 AT 08:45

Honestly, if you’re not already on a statin and a beta‑blocker, you’re neglecting basic standards of care for COPD patients with cardiac risk.

Haley Porter

October 8, 2025 AT 12:32

From a pathophysiological standpoint, the synergistic impact of hypoxemic vasoconstriction and systemic inflammatory cytokinemia accelerates endothelial dysfunction, precipitating atherogenesis.

Samantha Kolkowski

October 9, 2025 AT 16:18

Thanks for the thorough overview. It’s helpful to see both the science and the practical tips side by side.

Michael J Ryan

October 10, 2025 AT 20:05

Building on the long‑winded analysis, it’s worth noting that community‑based smoking cessation programs that incorporate cultural competency have shown up to a 50 % success rate, especially when paired with peer support groups. Additionally, integrating portable spirometry into primary‑care visits can catch early COPD changes before cardiac strain escalates.