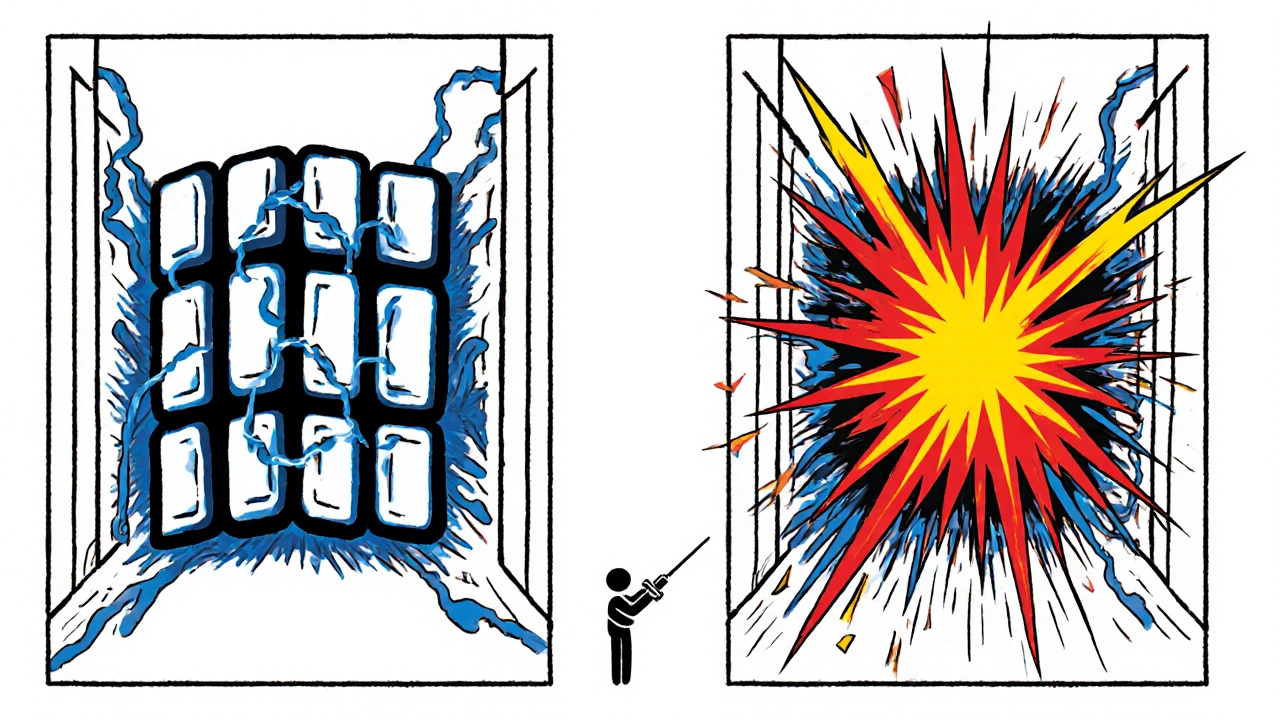

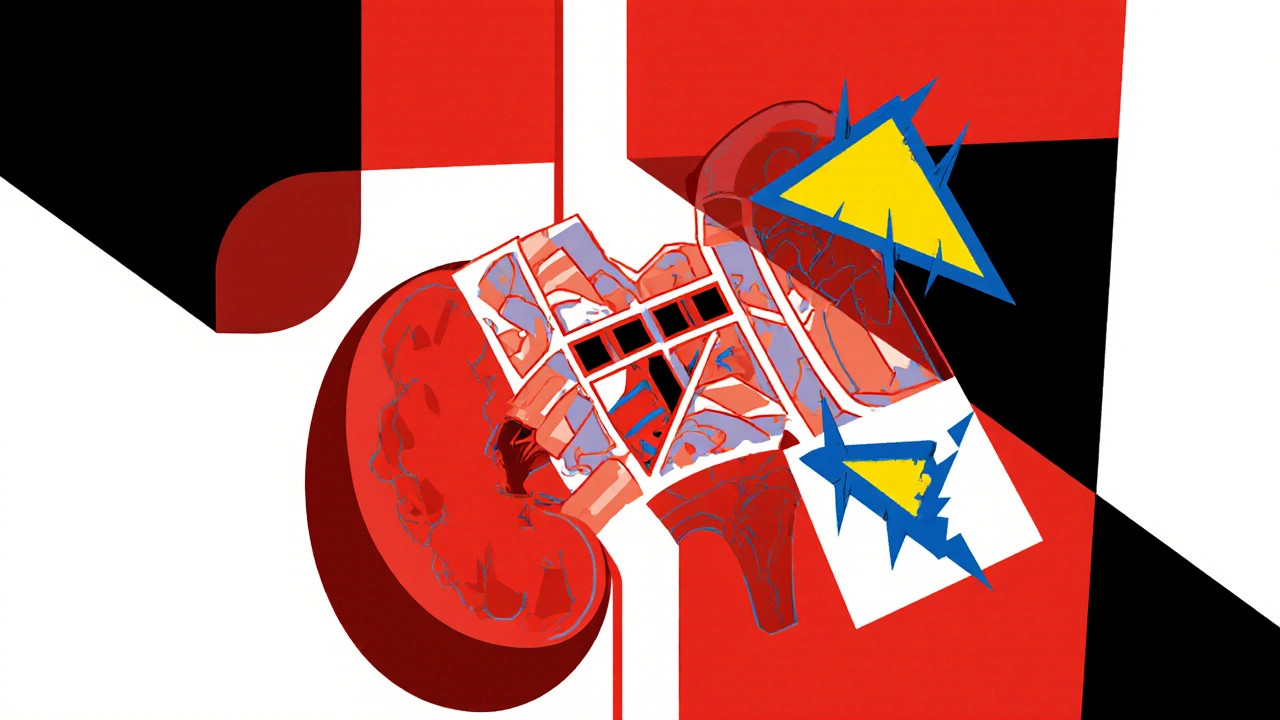

Imagine your kidneys as a network of microscopic sieves, filtering waste from your blood every minute. Now imagine your own immune system, designed to protect you, turning against those sieves and smashing them apart. That’s what happens in glomerulonephritis - a condition where your body’s defense system mistakenly targets the glomeruli, the tiny filtering units inside your kidneys.

What Exactly Are the Glomeruli?

The glomeruli are not just simple filters. Each one is a complex structure made of three layers: the innermost endothelial cells lined with a sugar coating called the glycocalyx, the middle glomerular basement membrane (GBM), and the outer layer of specialized cells called podocytes. These podocytes have foot-like projections that wrap around capillaries, forming gaps so small only water and waste can pass through - proteins and blood cells should stay behind. When glomerulonephritis strikes, immune cells and proteins invade this delicate system. Antibodies, complement proteins, or immune complexes pile up where they shouldn’t. This triggers inflammation, swelling, and scarring. As the filters break down, protein leaks into your urine (proteinuria), red blood cells escape (hematuria), and fluid builds up in your body, causing swelling in your ankles, face, or belly.Two Main Faces of Glomerulonephritis

Not all cases look the same. Glomerulonephritis typically shows up in two major forms: nephritic syndrome and nephrotic syndrome. Nephritic syndrome means your kidneys are inflamed and damaged from within. You’ll see blood in your urine, high blood pressure, reduced urine output, and rising creatinine levels - usually between 1.5 and 3.0 mg/dL. This form often follows infections like strep throat, especially in children. Post-streptococcal GN, for example, hits about 15% of kids with recent strep infections, but 95% recover fully within two months. Nephrotic syndrome is different. Here, the filters are so damaged that massive amounts of protein - more than 3.5 grams a day - slip into the urine. Your blood loses protein, so fluid leaks out into tissues, causing severe swelling. Cholesterol and triglycerides spike, often above 160 mg/dL. This form is more common in adults and can be caused by conditions like lupus or IgA nephropathy.The Most Common Types You Need to Know

There are several specific types of glomerulonephritis, each with its own trigger and pattern. IgA nephropathy is the most common form worldwide. It happens when IgA antibodies - normally fighting infections - clump together in the glomeruli. In North America, it affects about 2.5 people per 100,000 each year. Over 20 years, 20 to 40% of those with IgA nephropathy will develop kidney failure. C3 glomerulonephritis (C3G) is rarer but more aggressive. It’s not caused by antibodies, but by a runaway complement system - your body’s ancient immune alarm system. In C3G, the C3 protein builds up in the kidneys at levels 3 to 5 times higher than normal. About 60 to 70% of cases involve an autoantibody called C3 nephritic factor (C3NeF), which keeps the complement system stuck in “on” mode. Immune complex-mediated membranoproliferative GN (IC-MPGN) is caused by immune complexes - clumps of antibodies and antigens - lodging in the glomeruli. Biopsies show dense deposits in 95% of cases. Unlike C3G, IC-MPGN is often linked to chronic infections like hepatitis or autoimmune diseases like lupus. Lupus nephritis, which affects half to two-thirds of people with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), is another major type. With modern treatment, 70 to 80% of patients avoid kidney failure within 10 years - but without treatment, the outcome is far worse.

Why Do Podocytes Matter So Much?

Podocytes are the unsung heroes of the glomerulus. They don’t regenerate easily. Once they’re damaged, they can’t be replaced. That’s why immune attacks on podocytes are so dangerous. As Dr. Richard Johnson from the University of Colorado explained, podocytes have receptors that make them targets for inflammatory signals. They also produce their own inflammatory chemicals, creating a feedback loop of damage. When these cells die or pull away from the filter, protein leaks out - and the damage becomes permanent. This is why treatments that just suppress the whole immune system - like high-dose steroids - often fail. They don’t fix the root problem. They just slow the attack, often at the cost of serious side effects.How Is It Diagnosed?

There’s no blood test that confirms glomerulonephritis. The only way to know for sure is a kidney biopsy. A biopsy involves inserting a thin needle through the back to collect a tiny sample of kidney tissue. It’s safe for most people, but carries a 3 to 5% risk of bleeding or pain. The real challenge? Interpreting the sample. Nephropathologists - kidney pathologists - need 5 to 7 years of training to tell the difference between C3G, IC-MPGN, IgA nephropathy, and other variants under the microscope. New tools are helping. In 2023, the European Renal Association introduced a classification system that combines traditional biopsy findings with molecular biomarkers. This new method predicts treatment response with 85% accuracy - compared to just 65% using biopsy alone.Treatment: Steroids, Side Effects, and New Hope

For decades, the go-to treatment has been corticosteroids like prednisone. About 60 to 80% of patients respond at first. But here’s the catch: 30 to 50% of them experience treatment failure over time, and nearly 70% report major side effects. Weight gain? Common. Infections? 35% higher risk. Bone fractures? 28% of patients lose bone density within a year. One patient on a support forum described two vertebral fractures from prednisone in just 18 months. That’s why new drugs are changing the game. In 2023, the FDA gave breakthrough status to iptacopan, a drug from Novartis that blocks a key part of the complement system. In trials, it cut proteinuria by 52% in C3G patients - without the broad immune suppression of steroids. But there’s a catch: it costs about $500,000 a year. Other targeted therapies, like eculizumab, also show promise but are similarly expensive. The good news? More drugs are in development. The bad news? Access is wildly unequal. In low-income countries, patients have 90% less access to these new treatments than those in the U.S. or Europe.

Comments (9)

Nikhil Purohit

November 22, 2025 AT 17:38

Man, I never realized how crazy it is that our own body turns on itself like this. I had a cousin with IgA nephropathy - he was fine after a year, but the biopsy process? Absolute nightmare. They told him it felt like a needle stabbing through his back while he was awake. No anesthesia, just a ‘hold still’ and a ‘breathe deep.’ Still, at least he didn’t need steroids long-term. I’m glad they’re finally targeting the complement system instead of just nuking the whole immune system.

Debanjan Banerjee

November 23, 2025 AT 23:36

Let’s be clear: the real problem isn’t just the disease - it’s the diagnostic delay. Most patients see three doctors before someone orders a biopsy. In India, we have a 6-month average lag between first symptom and diagnosis. By then, podocyte loss is often irreversible. The new molecular classification system from the European Renal Association? Brilliant. But if your hospital doesn’t have a nephropathologist on staff, it’s useless. We need decentralized testing - point-of-care biomarkers, not just fancy labs in London or Boston.

Steve Harris

November 25, 2025 AT 02:25

As someone who works in clinical research, I’ve seen the shift firsthand. Steroids were the default for decades - and yes, they worked for some. But the side effects? Devastating. I had a patient who lost her job because she gained 60 pounds and couldn’t walk without pain. The real breakthrough isn’t iptacopan - it’s the *mindset* shift. We’re moving from ‘suppress everything’ to ‘target the exact malfunction.’ That’s precision medicine in action. The cost is insane, sure, but the alternative - dialysis at 35 - is worse.

Sandi Moon

November 25, 2025 AT 16:54

Let me ask you this: what if the entire narrative around glomerulonephritis is manufactured? The ‘immune system attacking itself’? That’s the official story - but have you ever wondered who benefits from the $4.7 billion market? Pharma giants fund the research, the ‘experts’ publish the papers, and suddenly we’re told we need $500k/year drugs. Meanwhile, the real cause? Glyphosate. Heavy metals. 5G-induced inflammation. The biopsy? A money-making racket. Podocytes don’t ‘die’ - they’re silenced by toxins. The FDA’s ‘breakthrough’ status? A corporate handshake. Wake up.

Kartik Singhal

November 27, 2025 AT 12:04

Bro, I read this whole thing and I’m just like… why are we even talking about this? 😴 I mean, IgA nephropathy? C3G? IC-MPGN? Who even remembers these acronyms? 😅 I just know I got protein in my pee and now I’m on steroids and my face looks like a balloon. The real takeaway? If your doctor doesn’t say ‘biopsy’ within 3 visits, find a new one. Also, iptacopan? $500k? Bro, I’m on a 9-to-5. Can I get a coupon? 🤡

Leo Tamisch

November 27, 2025 AT 21:07

There’s a metaphysical layer here, you know. The kidney - the organ of filtration - is being violated by the very system meant to protect. It’s not just biology; it’s symbolism. Our immune system, the embodiment of our identity’s defense, becomes the traitor. We live in an age of hyper-surveillance - our bodies, our data, our emotions - and yet we’re blind to the internal betrayal. Glomerulonephritis is the body’s cry against the noise of modern life. We treat it with chemicals. But what if the cure is silence? Stillness? Letting the body relearn its own harmony?

Simone Wood

November 29, 2025 AT 09:34

Okay but have you seen the side effects of prednisone? I had a friend who went from a 5’8” yoga instructor to a 220 lb moon face with bruises all over her legs. She got two vertebral fractures in 18 months. And then the doctors just said ‘oh well, you’re doing better’ - better? Better than what? Dying? I mean, sure, but at what cost? And now they want to give her a $500k drug? Are you kidding me? This system is broken. People are being turned into walking pharmacy ads.

Swati Jain

November 30, 2025 AT 00:54

Y’all are overcomplicating this. 😒 Glomerulonephritis? It’s just your immune system having a bad day after a bad infection. The ‘complex’ terminology? That’s just to make you feel like you need a PhD to understand your own body. Look - if you have protein in your urine and swelling? Go get a biopsy. Don’t wait for the ‘new targeted therapy.’ Do you know how many people in rural India die because they think it’s ‘just water retention’? Stop waiting for magic pills. Check your BP. Cut the salt. Drink water. And if your doc won’t order a biopsy? Find a new one. Simple. No jargon. No $500k. Just common sense.

Florian Moser

November 30, 2025 AT 01:46

This is actually one of the most hopeful medical stories I’ve read in a long time. The fact that we’re moving from ‘blunt force’ immunosuppression to targeted complement inhibition? That’s science evolving. I’ve worked with patients who were told they’d be on dialysis by 30 - now they’re hiking, working, living. It’s not perfect. The cost is insane. But the direction? Right. Keep pushing for access. Keep demanding equity. And if you’re reading this and you’re scared? You’re not alone. And we’re getting better - slowly, painfully, but better.