When you're fighting cancer, every dose matters. The difference between life and death isn't always in the diagnosis-it's in the details of the treatment. That’s why switching from a branded cancer drug to a generic version isn’t just a cost-saving move. It’s a clinical decision with real consequences. And when multiple drugs are combined-like in FOLFOX or R-CHOP regimens-the challenge of proving that generics work just as well becomes incredibly complex.

Why Bioequivalence Matters More in Cancer Treatment

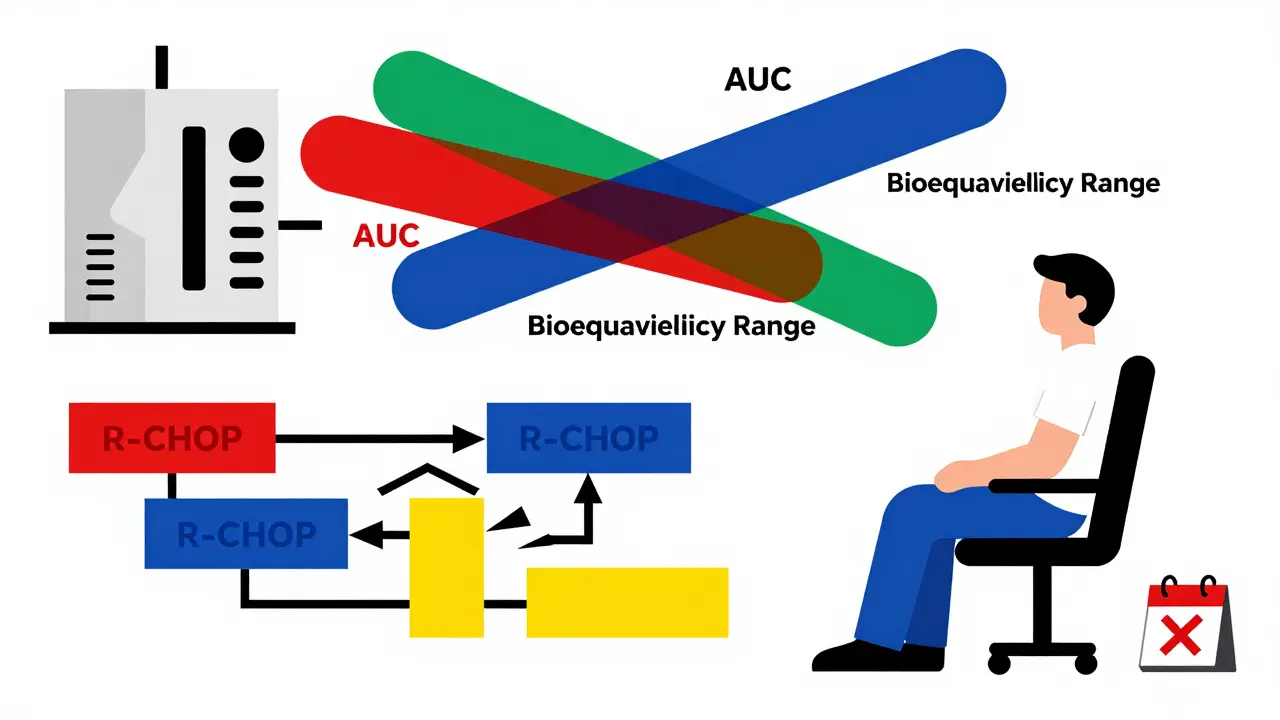

Bioequivalence means two drugs deliver the same amount of active ingredient into your bloodstream at the same rate. For most medications, if two pills have the same bioequivalence profile, they’re considered interchangeable. But cancer drugs? They’re different. Many have a narrow therapeutic index, meaning the dose that kills cancer cells is dangerously close to the dose that poisons healthy ones. A 10% drop in drug concentration might mean the tumor keeps growing. A 10% spike might cause organ failure. The FDA and EMA require generics to show that their drug’s absorption-measured by AUC and Cmax-falls within 80% to 125% of the branded version. That range works fine for blood pressure pills or antibiotics. For cancer? Not always. Drugs like methotrexate or vincristine need tighter limits-90% to 111%-to be safe. But even that’s not enough when you’re mixing multiple drugs.The Problem with Combination Therapies

About 70% of modern cancer treatments use combinations. Think of R-CHOP: rituximab (a biologic), cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone. Each component has its own bioequivalence requirements. But when you swap out one generic version of vincristine for another, or substitute a different generic of cyclophosphamide, you’re not just changing one drug-you’re changing the whole chemical dance. Drug-drug interactions become unpredictable. One generic version might release its active ingredient faster than the original. Another might bind differently to proteins in the blood. These tiny differences, harmless in a single-drug regimen, can amplify when combined. A 2023 study found that 42% of oncologists in the Gulf region worried about these interactions when generics were substituted individually instead of as a fixed combination. Even worse, some drugs in the mix are biologics-like rituximab or trastuzumab. These aren’t chemicals you can copy exactly. They’re made from living cells. So instead of bioequivalence, you need biosimilarity. That means running full clinical trials to prove safety and effectiveness. And even then, switching between biosimilars isn’t always automatic.Real Cases, Real Risks

It’s not theoretical. Oncology pharmacists are seeing it happen. One case documented on the ASCO Community Forum involved a patient on R-CHOP. After switching to a generic version of vincristine, the patient developed severe neuropathy-nerve damage that caused pain, numbness, and trouble walking. The generic had a different formulation that altered peak plasma levels. The dose was technically within bioequivalence range, but the timing of the spike was off. That’s enough to tip the balance. Another study at MD Anderson followed 1,247 patients who switched from branded Xeloda (capecitabine) to a generic version in combination with oxaliplatin. Their survival rates and side effects were nearly identical. That’s the success story. But it only worked because capecitabine is a small molecule with stable absorption and no major interactions. Not all drugs are that forgiving.

Cost vs. Safety: The Hard Choice

The math is clear: generics save money. Generic paclitaxel costs 60-80% less than the branded version. Trastuzumab biosimilars cut treatment costs by $6,000 to $10,000 per cycle. The U.S. could save $14.3 billion a year if generics were used wisely in oncology. But cost isn’t the only factor. A 2024 patient survey by Fight Cancer found that 63% of patients were worried about switching to generics in combination regimens. Over 40% said they’d ask for the brand-name drug-even if it meant paying more or waiting longer. Why? Because trust matters. Patients don’t want to be the first to try a new generic in a life-or-death regimen. And doctors? Many feel the same. Sixty-eight percent of hospital formulary committees require extra clinical data before approving generic substitution in combination therapies. That’s not because they’re against generics-it’s because they’ve seen what can go wrong.How the System Is Adapting

Regulators are catching up. The FDA launched the Oncology Bioequivalence Center of Excellence in 2024 to tackle these problems. The EMA is running pilot programs to test entire combination regimens-not just individual drugs. New guidelines from the International Consortium for Harmonisation now recommend tighter bioequivalence margins (90-111%) for narrow therapeutic index drugs in combinations. Some institutions are building tools to help. UCSF created a decision support algorithm that flags high-risk substitutions in real time. If a doctor tries to swap a generic vincristine in an R-CHOP regimen, the system pops up a warning. It reduced inappropriate substitutions by 63%. Pharmacists are getting better trained too. Nearly 80% of oncology pharmacy residencies now include over 40 hours of training on combination bioequivalence. They’re learning how to read formulation differences, understand food effects, and track supply chain issues.

What’s Next for Generic Cancer Drugs

The future isn’t just about more generics-it’s about smarter ones. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling is becoming a key tool. Instead of testing every combination in 30 healthy volunteers, scientists can simulate how different formulations interact in the body. This could cut development time and cost while improving accuracy. By 2030, the National Cancer Institute predicts that 35-40% of current combination therapies will need custom bioequivalence protocols. That means no more one-size-fits-all rules. Each combination may need its own testing standard. Meanwhile, supply chain problems keep happening. In 2023, generic cisplatin had 287 days of shortages across 14 manufacturers. When one generic runs out, switching to another-even if it’s bioequivalent-can disrupt treatment. That’s why some hospitals now require multiple approved generic suppliers for critical drugs.What Patients and Providers Should Do

If you’re on a combination regimen:- Ask if your drugs are part of a fixed-dose combination. If yes, don’t switch components unless the entire combo is replaced.

- Check the FDA’s Orange Book for therapeutic equivalence ratings. Only A-rated drugs are approved as interchangeable.

- Don’t assume all generics are the same. Even within the same drug, different manufacturers can have different release profiles.

- Report any new side effects after a switch-no matter how small. That data helps others.

- Use decision support tools if your hospital has them.

- Don’t substitute individual components in a combination unless you’ve verified the entire regimen’s equivalence.

- Document every substitution and its outcome. This builds the evidence base.

- Work with pharmacists to create institutional policies for generic use in oncology.

Comments (11)

Lance Nickie

January 13, 2026 AT 09:03

generic cancer drugs? more like generic chances of survival lol

jefferson fernandes

January 15, 2026 AT 07:49

Let me be clear: this isn’t just about cost-it’s about trust, precision, and human lives. The 80-125% bioequivalence window? That’s a casino bet when you’re dealing with vincristine or methotrexate. A 10% drop? Tumor keeps growing. A 10% spike? Kidneys shut down. We’re not talking about ibuprofen here. We’re talking about people who’ve already lost hair, energy, dignity-and now we’re gambling with their last shot? No. No no no. We need 90-111%, mandatory, across the board. And if that means slower approvals? Good. Better slow than dead.

I’ve seen pharmacists get yelled at for switching generics in R-CHOP. I’ve seen patients cry because their neuropathy got worse after a ‘bioequivalent’ swap. The FDA’s new Oncology Bioequivalence Center? Long overdue. UCSF’s decision tool? Brilliant. Why aren’t all hospitals using it? Because bureaucracy moves slower than a dying patient’s IV drip.

And don’t get me started on biosimilars. Rituximab isn’t a pill you can copy. It’s a living protein, made in cells, shaped by time, temperature, and luck. Swapping biosimilars like trading baseball cards? That’s not science-that’s negligence. We need full clinical trials for every switch. Not ‘it’s close enough.’ Not ‘the numbers look right.’ We need outcomes. We need survival curves. We need real data from real people-not healthy volunteers in a lab.

And yes, I know generics save billions. But if a patient dies because we cut corners? That’s not savings. That’s a moral bankruptcy. We need institutional policies. We need pharmacist-led audits. We need every substitution documented, tracked, and reviewed. No more blind swaps. No more ‘it’s the same drug.’ It’s not. Not in cancer. Not ever.

Nelly Oruko

January 16, 2026 AT 14:47

the bioequivalence range for cancer drugs should be tighter. period.

Diana Campos Ortiz

January 17, 2026 AT 08:28

I had a friend on R-CHOP who switched generics and got neuropathy. No one warned her. She thought it was just chemo side effects… until she couldn’t button her shirt. I’m so glad someone’s finally talking about this. Please, if you’re a provider-ask your pharmacist. Don’t assume.

Milla Masliy

January 18, 2026 AT 11:13

As someone who grew up in a household where medicine was a luxury, I get the need for generics. But I also watched my uncle’s oncologist pause for 20 minutes before approving a switch-even though the cost was half. He said, ‘I don’t trust the timing.’ And he was right. Cancer doesn’t wait. Neither should we rush. Maybe the answer isn’t more generics-it’s smarter ones. Ones that come with real-time monitoring, like the UCSF tool. Maybe we need to treat combination regimens like a symphony-each instrument must play in perfect harmony. One wrong note, and the whole piece collapses.

And honestly? Patients deserve to know the brand name, even if they’re paying out of pocket. Transparency isn’t a luxury-it’s a lifeline.

John Pope

January 19, 2026 AT 13:16

Let’s be brutally honest: the entire regulatory framework for oncology generics is a Kafkaesque farce. We’ve got regulators applying antibiotic logic to drugs that kill neurons. We’ve got hospitals substituting vincristine like it’s a discount coffee creamer. And we’ve got patients-people who’ve already survived chemo, lost their hair, buried friends, cried in parking lots-being treated like lab rats in a cost-cutting experiment. This isn’t healthcare. It’s pharmacological Russian roulette with a side of corporate PR.

And don’t give me that ‘PBPK modeling is the future’ nonsense. Modeling doesn’t feel neuropathy. Modeling doesn’t vomit blood. Modeling doesn’t watch their child’s face turn gray because the generic version of doxorubicin peaked 17 minutes too early. Real people. Real pain. Real consequences.

Meanwhile, the pharmaceutical industry is laughing all the way to the bank. They’ll sell you a $12,000 branded drug, then slap a ‘bioequivalent’ label on a $3,000 version and call it progress. But here’s the truth: if your drug can’t be trusted in a combination, it shouldn’t be on the shelf. Period. We need FDA-mandated combo-specific equivalence testing. Not ‘individual drug approval’ nonsense. We need to treat regimens as single entities. Because in oncology, the whole is not greater than the sum-it’s more dangerous.

And to those who say ‘patients want cheaper options’? Yeah, they do. But they want to live more. So give them choice. Give them transparency. Give them data. Don’t give them a gamble wrapped in a pill.

Clay .Haeber

January 20, 2026 AT 00:00

Oh wow, so now we’re treating cancer like a chemistry set? ‘Oh, this generic vincristine is 82% bioequivalent-close enough!’ Meanwhile, the patient’s nerves are screaming, their liver is staging a coup, and the doctor’s just shrugging because ‘it’s within range.’ What a world. We’re not fixing healthcare-we’re optimizing for shareholder dividends while patients become statistical outliers.

And let’s not pretend biosimilars are ‘the same.’ Trastuzumab is made by living cells. You can’t copy a living thing like you copy a PDF. That’s not science-that’s alchemy with a FDA stamp. If you think switching biosimilars is safe without full trials, you’ve been reading too many investor reports and not enough patient journals.

Also, 63% of patients are worried? Good. They should be. If you’re not terrified of switching cancer drugs, you’re either lying or dead.

Adam Vella

January 21, 2026 AT 07:04

The current bioequivalence paradigm, predicated upon the 80–125% confidence interval derived from pharmacokinetic studies in healthy volunteers, is fundamentally misaligned with the clinical realities of oncologic therapeutics. The narrow therapeutic index of cytotoxic agents, compounded by synergistic and antagonistic drug-drug interactions within polypharmacy regimens, renders this statistical tolerance zone clinically inadequate. Empirical evidence, as cited from MD Anderson and ASCO, demonstrates that even minor perturbations in Cmax and AUC-within the so-called acceptable range-can precipitate clinically significant deviations in tumor response and systemic toxicity. Therefore, the regulatory framework must evolve toward regimen-specific bioequivalence criteria, incorporating physiologically based pharmacokinetic modeling and real-world outcome surveillance. The absence of such a paradigm constitutes a systemic failure of translational medicine.

Angel Molano

January 22, 2026 AT 01:33

Stop pretending generics are safe. You’re playing God with people’s lives. If you switch a cancer drug, you’re not saving money-you’re committing negligence. And if you’re a doctor who lets it happen, you’re part of the problem.

Vinaypriy Wane

January 23, 2026 AT 01:25

Thank you for writing this. In India, we see this every day-families choosing generics because they have no choice. But I’ve seen patients suffer because the generic wasn’t just cheaper-it was different. The timing, the fillers, the release profile… it all matters. We need global standards. Not just FDA or EMA. We need WHO guidelines that say: ‘If it’s for cancer, it must be tested as a combo, not alone.’ And we need to train pharmacists everywhere-not just in the US-to understand this. Lives depend on it.

John Pope

January 23, 2026 AT 01:37

Someone just said ‘patients want cheaper options.’ Yeah, they do. But they also want to survive. You can’t have both if you’re cutting corners. The only way this works is if we treat combination regimens as single entities-like a drug cocktail. If you change one ingredient, you’re making a new cocktail. And that needs a new safety profile. The FDA’s new center? Good start. But they need teeth. They need to reject generics that aren’t tested in combo. No more ‘it’s bioequivalent’ as a free pass. That’s not science. That’s corporate laziness dressed up as progress.