What Are Arrhythmia Procedures?

When your heart beats too fast, too slow, or irregularly, it’s called an arrhythmia. For many people, medications help. But if pills don’t work-or cause side effects-doctors turn to procedures that fix the problem at its source. Two main options stand out: catheter ablation and device therapy. These aren’t open-heart surgeries. They’re targeted, minimally invasive, and often life-changing.

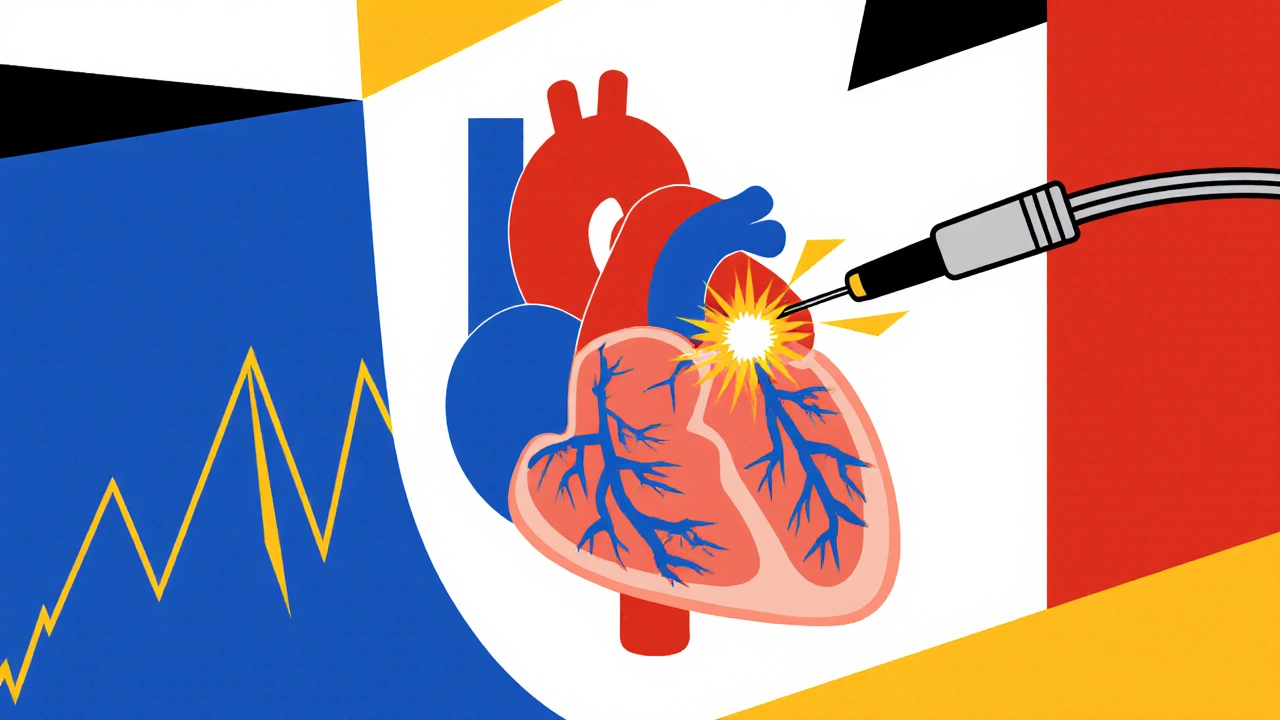

Catheter Ablation: Zapping the Problem at the Source

Catheter ablation works like a precision electrician fixing a short circuit in your heart. A thin tube (catheter) is threaded through a vein in your groin or neck and guided to the heart. Once it reaches the spot causing the abnormal rhythm, it delivers energy-either heat (radiofrequency) or cold (cryoablation)-to destroy tiny areas of tissue that are sending mixed signals.

This isn’t new. Doctors started doing this in the late 1980s. But today’s tools are smarter. Modern catheters like the THERMOCOOL SMARTTOUCH measure how firmly they’re touching heart tissue. They also track how long energy is applied and how much power is used. This combo is called the Ablation Index. It tells the doctor if the lesion is strong enough to stop the arrhythmia for good.

For atrial fibrillation (AFib), the most common target is the pulmonary veins. These veins often trigger erratic signals. The procedure creates a ring of scar tissue around them-called pulmonary vein isolation-to block those signals. Studies show this works in 71% of patients after one year with contact force catheters, compared to 58-65% with older tools.

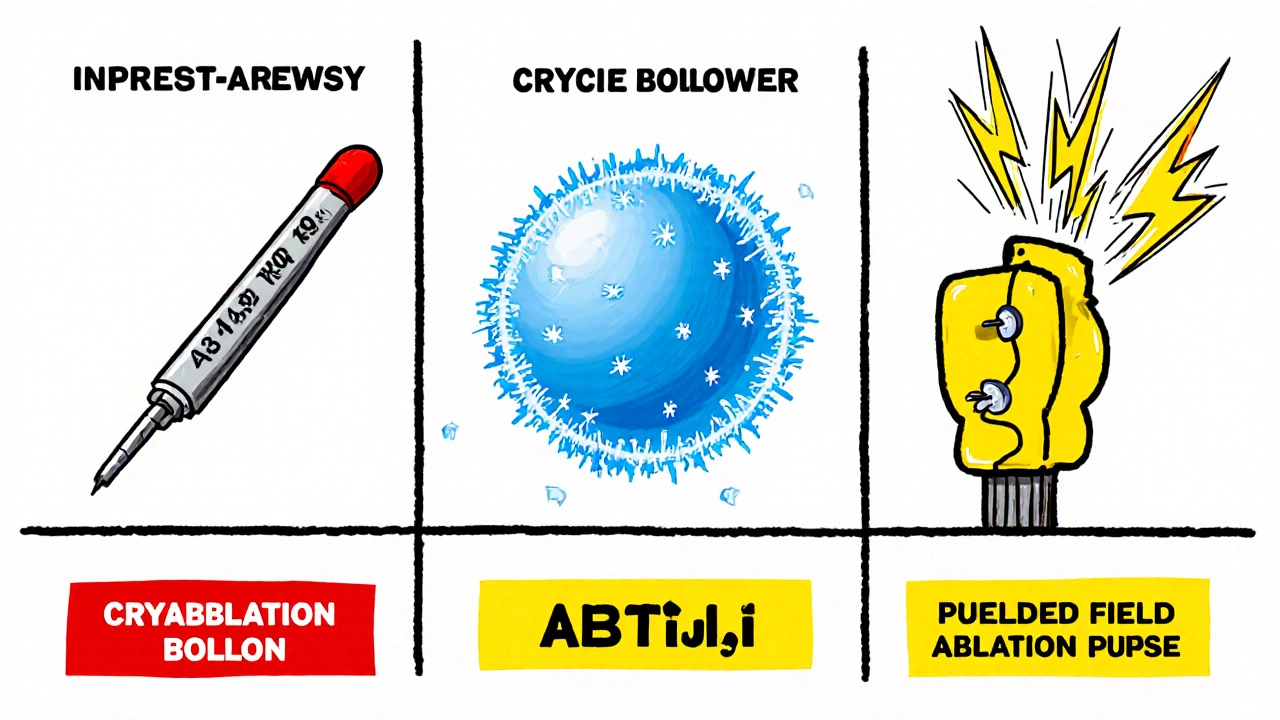

Another option is cryoablation, using freezing gas to freeze the tissue. It’s faster-often under two hours-and easier for doctors to learn. But it’s mostly used for AFib, not other rhythm problems. Laser ablation exists too, with a tiny camera built into the catheter so the doctor can see exactly where they’re treating. But it takes longer and isn’t as widely used.

Device Therapy: Pacemakers and ICDs for When the Heart Needs a Helper

Not all arrhythmias can be fixed by burning or freezing tissue. Some hearts just don’t pump well enough, or they stop suddenly. That’s where devices come in.

A pacemaker is a small box, about the size of a stopwatch, implanted under the skin near the collarbone. Wires run into the heart to deliver tiny electrical pulses that keep the rhythm steady. It’s perfect for slow heartbeats (bradycardia) or when the heart’s natural wiring fails.

For people at risk of sudden cardiac arrest-often due to weak heart muscle or prior heart attacks-an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) is used. It does everything a pacemaker does, but it can also deliver a strong shock to restart the heart if it goes into a deadly rhythm like ventricular fibrillation. ICDs have saved countless lives. In fact, patients with heart failure and reduced pumping ability who get an ICD cut their risk of sudden death by up to 40%.

Some newer devices combine both functions-pacemaker and ICD-in one unit. Others, called cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) devices, help both sides of the heart beat in sync, improving blood flow in patients with heart failure.

Ablation vs. Medications: The Numbers Don’t Lie

Many patients start with drugs. But studies show ablation beats medication in almost every way.

- After one year, patients who had ablation were 58% less likely to have another AFib episode than those staying on pills.

- They were 44% less likely to be hospitalized for heart problems.

- For patients with heart failure and AFib, ablation improved heart pumping ability by over 5% on average-something meds rarely do.

- One major study found these patients had a 48% lower risk of dying over the next few years after ablation.

And it’s not just physical. People report less anxiety, better sleep, and more energy. One patient on a heart support forum said he went from daily palpitations to zero episodes after his second ablation. "The mental relief is as valuable as the physical," he wrote.

But ablation isn’t magic. About 8% of patients have complications. The most serious is cardiac tamponade-fluid building up around the heart. It happens in 1.2% of cases. Other risks include damage to blood vessels, bleeding, or, rarely, injury to the esophagus or phrenic nerve (which controls the diaphragm). These are rare, but real.

Which Ablation Technology Is Best?

Not all catheters are created equal. Here’s how the top options stack up:

| Technology | Energy Type | Average Procedure Time | 12-Month Success Rate | Key Advantages | Key Risks |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| THERMOCOOL SMARTTOUCH (RF) | Radiofrequency | 150-180 min | 71% | Most effective for complex cases; uses Ablation Index for precision | Higher risk of esophageal injury; longer procedure |

| Arctic Front Advance (Cryo) | Cryoablation | 90-120 min | 65% | Faster, easier learning curve; lower risk of blood clots | 1.5-3% risk of phrenic nerve injury |

| HeartLight (Laser) | Laser | 180 min | 68% | Real-time visualization; precise lesion placement | Longest procedure; limited availability |

| Farapulse (PFA) | Pulsed Field | 76 min | 85.9% | Newest tech; no heat or cold; no esophageal damage | Very new; long-term data still being collected |

The THERMOCOOL SMARTTOUCH with Ablation Index is currently the gold standard for success rates. But cryoablation is growing fast because it’s faster and simpler. The newest player, pulsed field ablation (PFA), uses electric pulses instead of heat or cold. It’s faster, safer for nearby tissues, and just got FDA approval in 2023. Early results show 86% freedom from AFib at one year-with no esophageal injuries in over 150 patients. It’s not everywhere yet, but it’s the future.

Who Gets These Procedures?

Guidelines say catheter ablation should be offered to patients with symptomatic AFib who haven’t responded to at least one antiarrhythmic drug. That’s a Class I recommendation-meaning it’s strongly supported by evidence.

For people with heart failure and AFib, ablation isn’t just an option-it’s often the best choice. Studies show it improves heart function, exercise capacity, and survival. The 2023 JAMA study found patients who had ablation also had less depression and anxiety, likely because they weren’t constantly worrying about their next arrhythmia.

Device therapy is recommended for:

- Slow heart rates (pacemaker)

- High risk of sudden cardiac arrest (ICD)

- Heart failure with uncoordinated pumping (CRT device)

But not everyone qualifies. If your heart is too damaged, or if you have other serious illnesses, doctors may recommend managing symptoms instead.

Cost, Access, and the Future

Catheter ablation costs between $16,000 and $21,000 upfront. That’s more than a year’s worth of medication. But over time, it pays off. Because patients need fewer hospital visits, fewer drugs, and fewer emergency trips, ablation becomes cheaper than meds after about 3 to 8 years.

Medicare in the U.S. pays about $18,500 per procedure. In Europe, it’s around €12,000-15,000. The global market for these devices is growing fast-projected to hit $6.2 billion by 2028. But access isn’t equal. Rural areas have 60% fewer centers that can do these procedures than big cities. That’s a real problem.

What’s next? AI tools are being developed to help doctors see exactly where lesions are forming during the procedure. By 2025, software like Medtronic’s AI Path will give real-time feedback on tissue damage. Pulsed field ablation will become more common. And by 2030, experts predict ablation will become the first-line treatment for most people with symptomatic AFib-not just a backup.

Recovery and What to Expect

Most people go home the same day or the next. You’ll feel sore at the catheter insertion site. Some have mild chest discomfort or skipped beats for a few weeks-that’s normal as the heart heals. You’ll need to avoid heavy lifting for a week or two.

It can take 2-3 months for the full effect. Some patients need a second procedure. About 20-30% of people with persistent AFib will need a repeat ablation. But for many, it’s a one-time fix. One patient said, "I stopped all my meds after the procedure and started cycling again. I didn’t think I’d ever feel that normal again."

Frequently Asked Questions

Is catheter ablation safe?

Yes, for most people. Major complications happen in about 8% of cases, with cardiac tamponade being the most serious (1.2% risk). Newer tools like contact force catheters and pulsed field ablation have reduced these risks by 30-40%. The procedure is much safer today than it was 10 years ago.

Will I be awake during the procedure?

Most patients are sedated but not fully asleep. You’ll be relaxed and may feel pressure or warmth in your chest, but not pain. Some centers offer general anesthesia, especially for longer or more complex cases.

How long does recovery take?

Most people return to light activities within 2-3 days. Avoid heavy lifting or strenuous exercise for 1-2 weeks. Full healing takes 2-3 months. Some patients feel better right away; others notice gradual improvement over weeks.

Can I stop taking blood thinners after ablation?

Not always. Even if your rhythm is normal, your stroke risk may still be high depending on your age, history of heart failure, or other conditions. Doctors usually keep patients on blood thinners for at least 2-3 months after ablation, then reassess. Never stop them without talking to your doctor.

Do I need a pacemaker after ablation?

Rarely. Ablation targets abnormal pathways, not the heart’s natural pacemaker. But if the procedure accidentally damages the heart’s normal electrical system-which happens in less than 1% of cases-you might need a pacemaker. This is uncommon with modern techniques.

What’s the difference between a pacemaker and an ICD?

A pacemaker treats slow heart rates by sending small pulses to keep your rhythm steady. An ICD does that too, but it can also deliver a strong shock if your heart goes into a life-threatening rhythm. ICDs are for people at risk of sudden cardiac arrest; pacemakers are for slow rhythms.

Is pulsed field ablation better than radiofrequency?

Early data says yes-for safety, not necessarily effectiveness. PFA uses electric pulses instead of heat or cold, so it doesn’t damage nearby tissues like the esophagus or nerves. It’s faster (under 80 minutes) and has no reported esophageal injuries in trials. But it’s new, and long-term results are still being studied. It’s not yet the standard, but it’s the fastest-growing option.

Can I exercise after ablation?

Yes, but slowly. Avoid intense workouts for 1-2 weeks. Light walking is encouraged. Many patients return to sports like cycling, swimming, or running within 3 months. One patient returned to competitive cycling just 3 months after cryoablation. Listen to your body and follow your doctor’s advice.

Next Steps If You’re Considering Treatment

If you’re on meds and still having symptoms, talk to your cardiologist about a referral to an electrophysiologist-a heart rhythm specialist. They’ll review your history, run tests like an ECG or Holter monitor, and decide if ablation or a device is right for you.

Ask about:

- Which ablation technology they use most often

- How many procedures they do each year

- Whether they use contact force or Ablation Index

- What their success and complication rates are

Don’t assume meds are your only option. For many, ablation or a device is the path back to a normal life-no daily pills, no constant fear of palpitations, and no more skipping activities because you’re worried about your heart.

Comments (13)

Sammy Williams

November 20, 2025 AT 20:08

I had ablation last year and honestly? Life changed. No more meds, no more panic attacks when my heart skips. Just went hiking last weekend like it was nothing. Seriously, if meds aren't working, don't wait. Talk to an EP.

Julia Strothers

November 21, 2025 AT 13:28

They say it's 'minimally invasive' but let's be real-this is Big Pharma’s way of selling you a $20k device so they can keep charging for follow-ups. They don’t want you cured, they want you dependent. And don’t get me started on the FDA approving PFA without 10-year data. This is all a scam.

Erika Sta. Maria

November 23, 2025 AT 09:07

i read this and thought… if ablation is so good why dont we just zap all hearts? like… why not prevent arrhythmia before it happens? its like fixing a leaky roof by painting over the whole house. also… pulsed field? sounds like sci fi. are we sure its not just 5g radiation? i think the esophagus is just being silenced… not protected.

Nikhil Purohit

November 23, 2025 AT 15:53

This is actually super helpful. I’ve been on beta-blockers for 3 years and still get fluttering. I didn’t realize ablation could improve heart function too-thought it was just about rhythm. Gonna book an EP consult this week. Any tips on what questions to ask?

Steve Harris

November 24, 2025 AT 13:59

I’ve worked in cardiac tech for 15 years. The data here is solid. Ablation success rates with contact force catheters have genuinely improved outcomes. That said, patient selection matters more than the tech. A 75-year-old with multiple comorbidities? Device therapy might be the smarter play. Don’t chase the shiny new thing if you’re not a good candidate.

Michael Marrale

November 25, 2025 AT 14:19

Wait… so if you get an ICD, does that mean they’re tracking your heart 24/7? Like… is the government or the hospital watching your heartbeat? I heard they can trigger it remotely. Is that true? My cousin’s ICD went off in the middle of the night-she says it felt like a truck hit her. Should I be scared?

David vaughan

November 27, 2025 AT 04:26

I had cryoablation… and honestly? The worst part was the recovery. Not the procedure-just the weird chest tightness for weeks. I kept thinking it was failing… but my doc said it was just healing. Also, I cried after my first walk without dizziness. I didn’t know I’d forgotten what normal felt like. Thank you for writing this.

Cooper Long

November 28, 2025 AT 19:41

The clinical evidence supporting catheter ablation as a first-line intervention for symptomatic atrial fibrillation is now robust. The shift from pharmacological suppression to anatomical substrate modification represents a paradigm evolution in electrophysiological management. Cost-effectiveness models corroborate long-term savings.

Sheldon Bazinga

November 30, 2025 AT 05:54

Pulsed field ablation? Sounds like a buzzword for 'we don't know what we're doing but we got a grant.' Also, why is every article about this written like it's a miracle cure? You know what's real? The guy in the ER with a hole in his heart because they zapped too hard. They don't tell you that part.

Logan Romine

December 1, 2025 AT 19:13

So we're just gonna zap our way to health now? 🤔 Next they'll be selling 'soul ablation' for existential dread. I mean… if your heart's out of sync… maybe it's not the tissue. Maybe it's your life? Just sayin'. Also, PFA? Pulsed Field Abduction? Sounds like a sci-fi movie. 🤖💥

Chris Vere

December 2, 2025 AT 06:36

In Nigeria we dont have access to this. We use pills and hope. I read this and felt both hope and sadness. Someone should bring these tools here. Not just for the rich. Heart dont care where you live

Pravin Manani

December 2, 2025 AT 17:08

The Ablation Index is a game-changer-quantifies lesion quality via contact force, time, and power. This reduces recurrence by standardizing lesion delivery. PFA’s non-thermal mechanism spares collateral tissue-critical for structures like the phrenic nerve. Long-term data pending, but early AF-free rates are unprecedented.

Mark Kahn

December 4, 2025 AT 06:18

If you’re reading this and still on meds with symptoms-don’t give up. Talk to an electrophysiologist. It’s not a last resort. It’s a next step. You deserve to feel normal again. I’ve seen too many people wait too long. You got this.